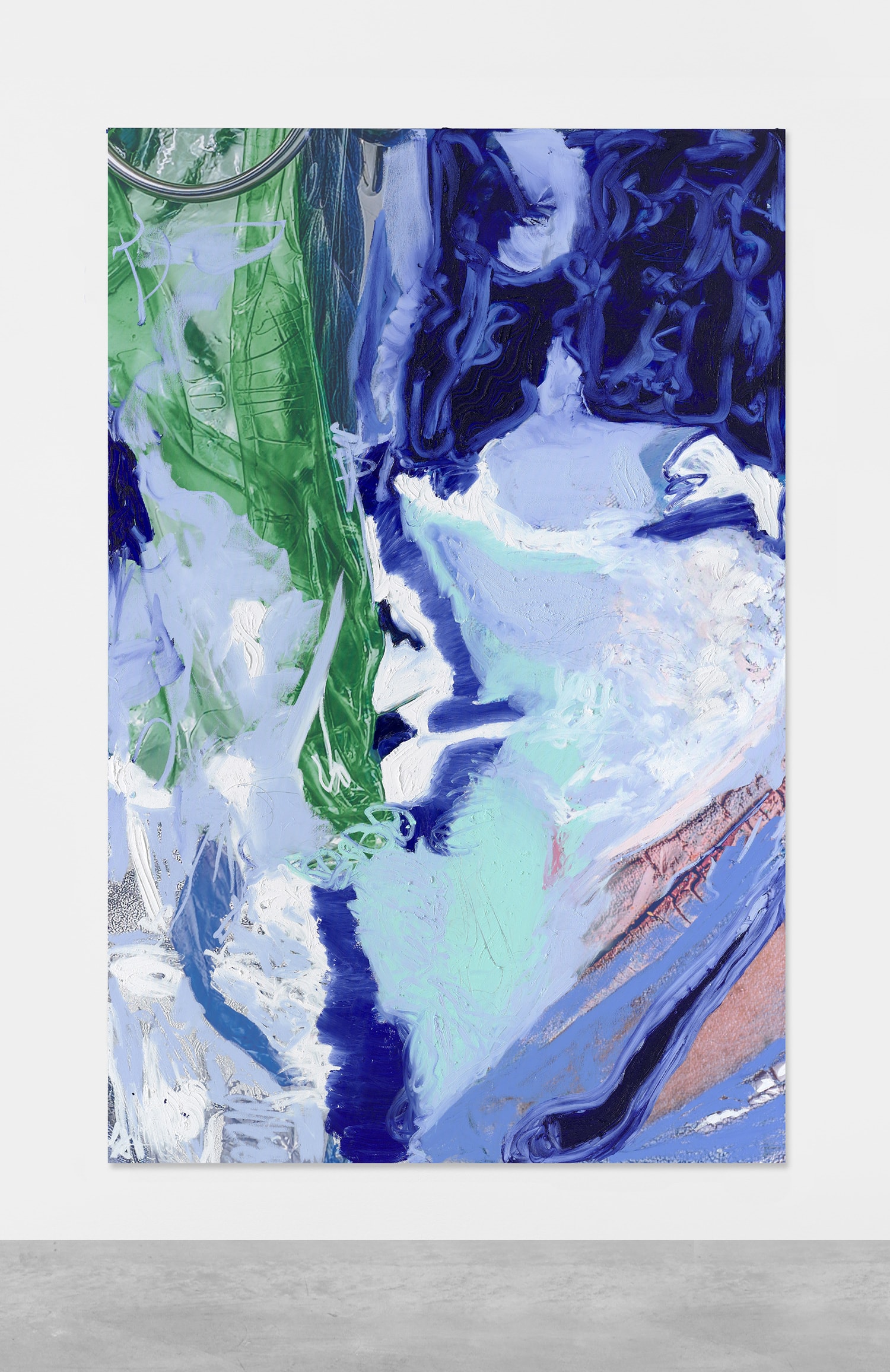

The paintings in WET SLIT are a continuation of Huanca’s work with the body and its epidermis. Her process for creating the paintings usually begins with images of her painted performers, which are then blown up and printed onto canvas. Layers of time accumulate as over the This frozen snapshot of the performer is then covered over with layers of paint and rough textural sand, allowing sediments of time to accumulate. In some of the paintings the body is almost entirely effaced in strokes of green and blue, while in others the body emerges coyly, a foot that hides behind a thick layer of impasto blue and white. While often her work is spoken of as dealing with the process of cosmetic adornment – the many fixtures we attach to ourselves – Huanca’s work reinforces the notion of the skin as the body’s barrier. We do not only armour our bodies with clothing, but the skin itself is a fortification, albeit a porous one. It is our protection from the world and it is the at which the physical world interacts with us. In Huanca’s painting, this receptive sensitivity of the skin’s barrier is felt on the surface of the canvas, the paint clustering in places like pressure points on the skin.

Going downstairs into the basement gallery, the transition is as abrupt as travelling into another realm. Moving from the white cube space upstairs into a darkened underground room with dramatic spotlights pointed towards a wall of paintings and a singular screen, I am reminded of the mythological story of Psyche who was impelled to go into the underworld to collect a piece of Persephone’s beauty, to bring up into the world of mortals. The basement – traditionally seen as the nether region of architecture – is carpeted and conveys intimacy in its darkness. Unlike the low-level toxic smell of plastic, the fumes of palo santo (holy wood that is used for purification and ritual, native to the Yucatán Peninsula) spill into the space alongside a loop of nature sounds, filling the basement with an elegant counterpoint to upstairs.

Huanca has called this part of the exhibition, the “death cocoon space”, a zone which, like a womb, holds a darkness from which new life emerges. I think about this as I face the wall upon which three large-scale abstract paintings shown on top of digital prints lightly touch along each other’s sides. Their edges are so proximate that my body almost aches in jealousy at the ease of these objects and their casual proximity. I wonder how Huanca’s performers presently exist in a world of social distancing, where the openness of skin is equivalent to a threat to life. And, quietly, in amongst the visceral installation of the “death cocoon space”, I try to imagine what life will emerge from this current death that the world is suffering… What forms of proximity might be born from this space of distance?