IN__What made you decide to move out of New York to the suburbs? Were you working alone at this time? What are some of the most notable changes you made in your work as a result of this experience and how had you felt restricted previously?

HB__I live much beyond the suburbs in a depressed river city in the Hudson Valley called Poughkeepsie. My husband (The painter Jason Fox) and I moved out of New York City because we could no longer afford to live there. I started using clay and as I mentioned before the distance from the city liberated me to follow my gut.

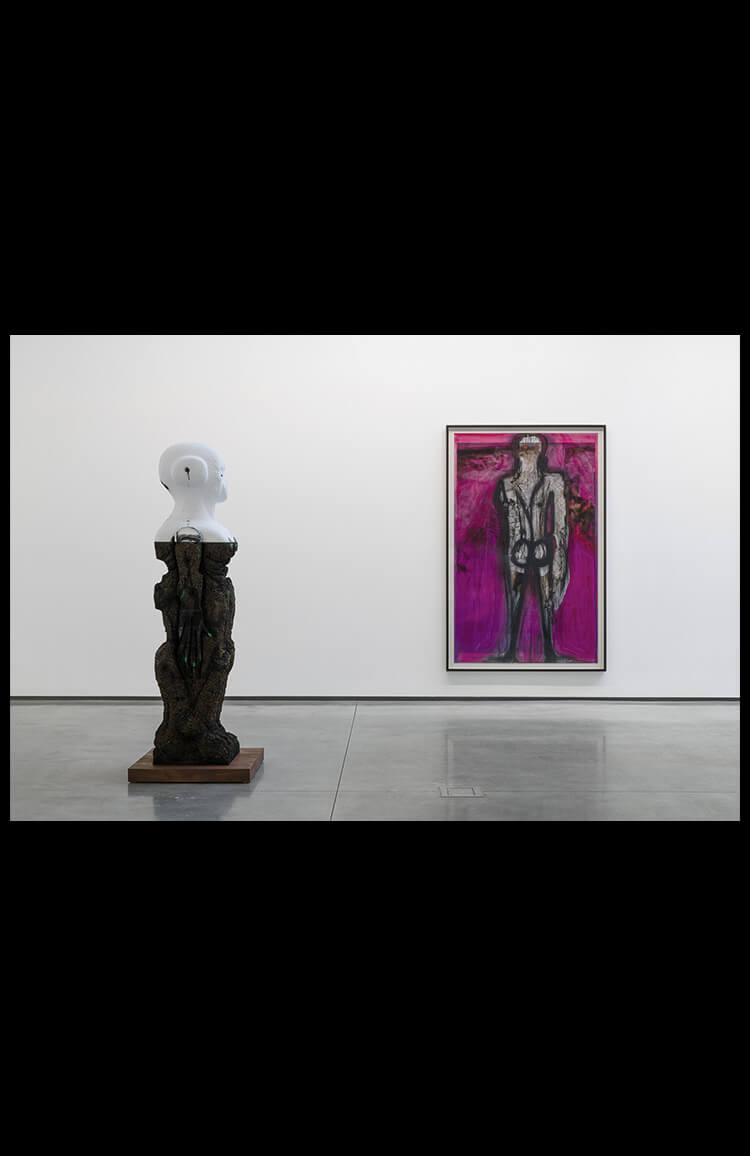

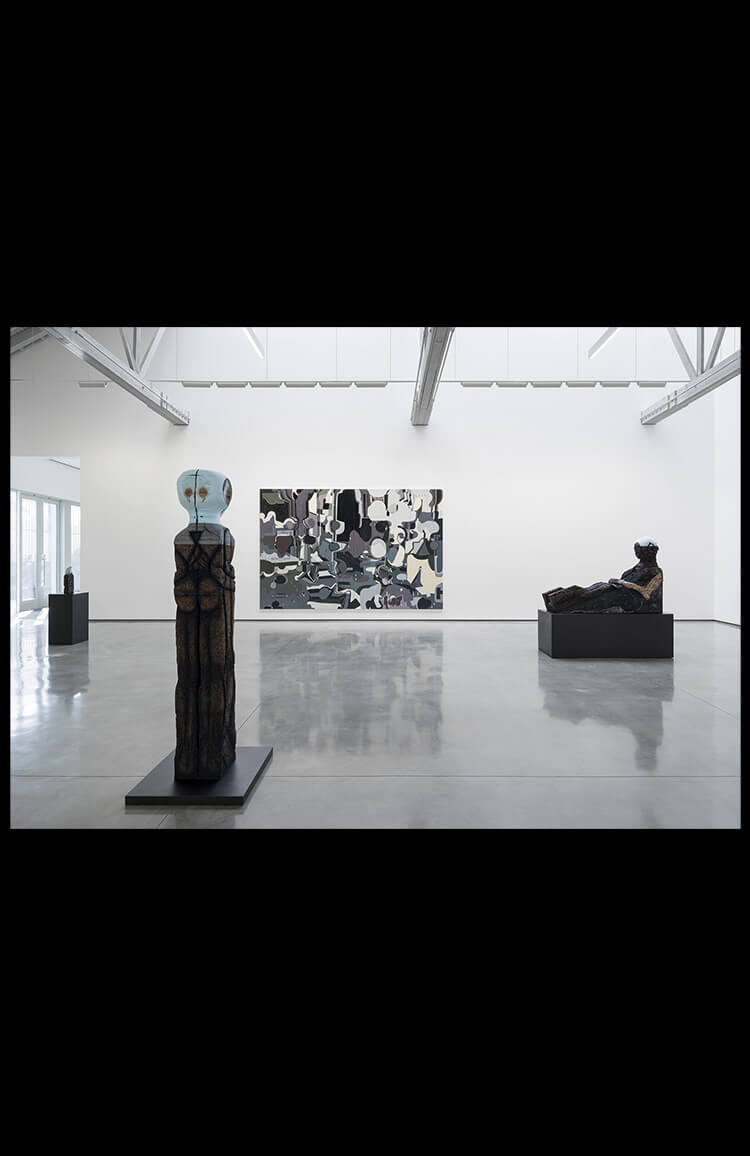

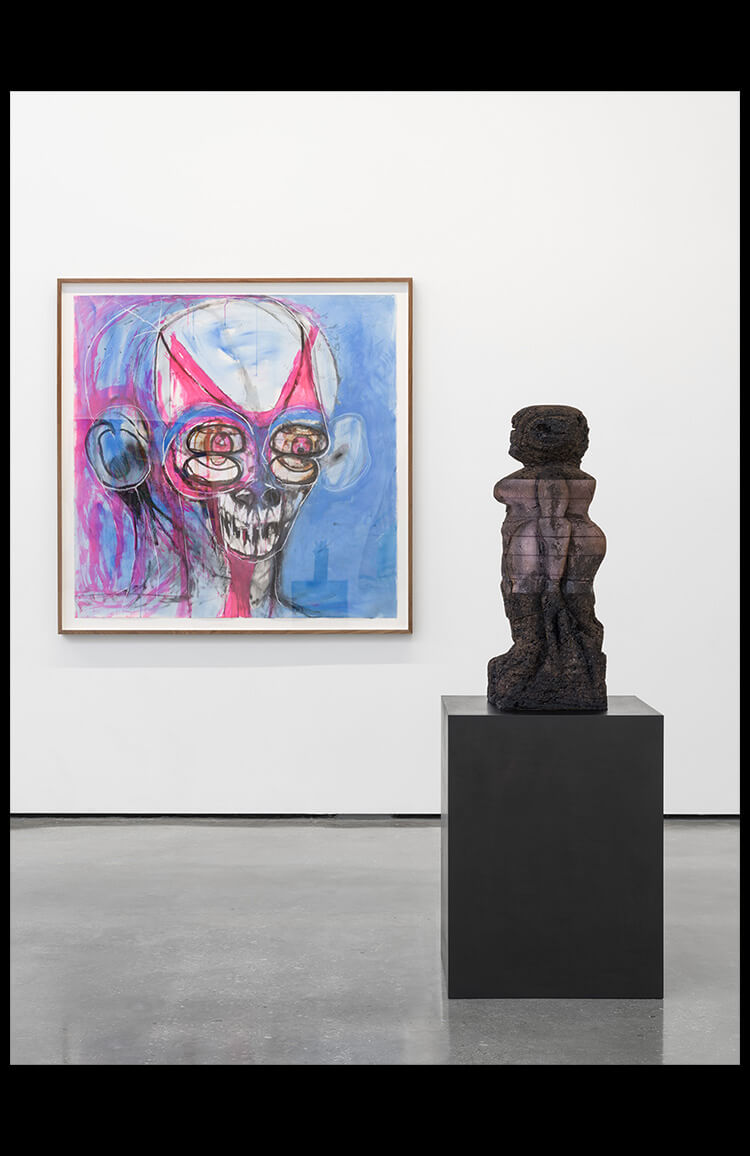

IN__You are predominantly known for your figurative sculptures, but you also make large scale drawings, using ink, collage and pencil over photographic prints and paper. How do these two disciplines come together in your work? Do the sculptures grow out of the drawings or do you see them as separate, made alongside one another?

HB__Before I started making three-dimensional work I was mainly painting and drawing. Drawing is something you can do in a small space and I turned to it when I didn’t have a studio. I have been interested in portraiture since I was in high school and that has now become more developed. I have also been interested in collage and assemblage since I was an undergraduate at college. The sculptures and drawings are not directly related, as in I don’t make drawings for the sculptures but working on them side by side has informed them in a more interesting and unpredictable way. I started using wild life images from calendars around 2013 and have developed that in a more serious way. Playing with the scale of the drawings has also been successful.

IN__How do you choose your source imagery, for example the wild life images? Do you feel any particular connection to them?

HB__I am drawn to images of all kinds and especially those of animals. The use of animal imagery seems appropriate as we are in the midst of a mass extinction of animal life and calendars are a cheap source for that kind of imagery.

IN__How can you tell when a drawing, painting or sculpture is successful?

HB__It comes with time and experience and knowing your work.

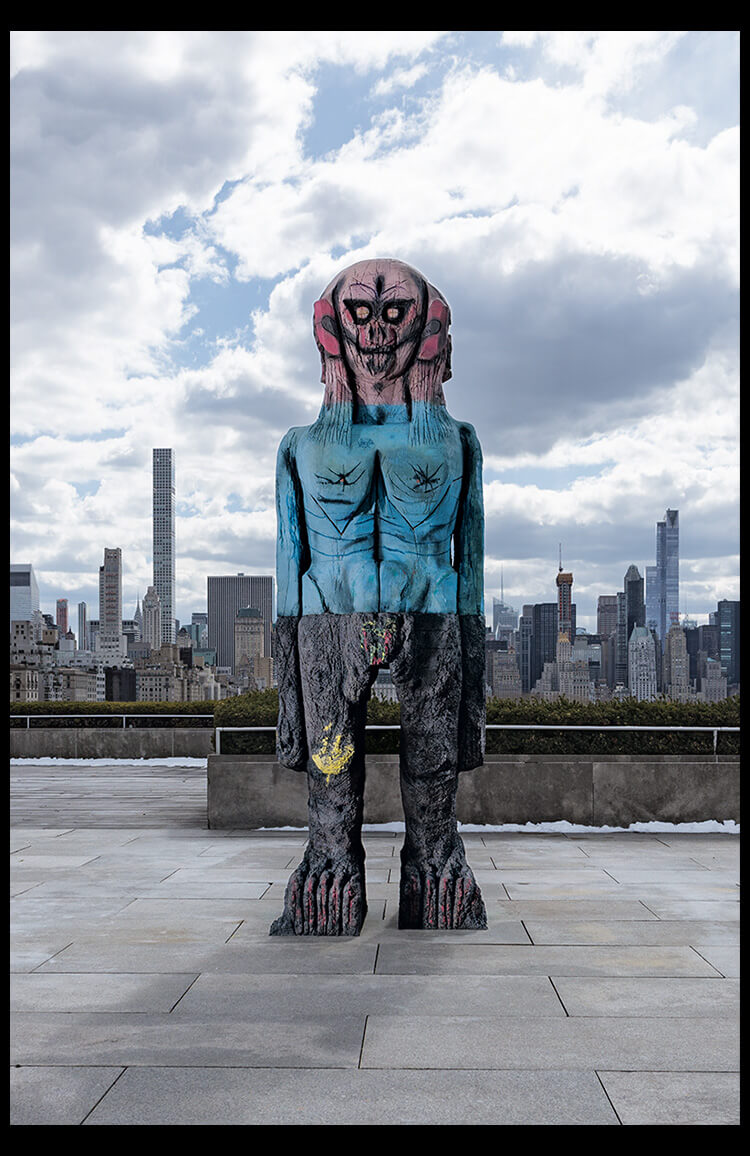

IN__You were brought to wider public attention with your commissioned work We Come in Peace, installed on the roof terrace of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2018. The installation consists of two enormous, roughly hewn figures cast in bronze; one standing and the other, draped in what looks like a tarpaulin with only its hands visible, lying prone before it, seemingly in a state of worship. Can you talk a bit about this piece and why you think it struck a particular chord with people?

HB__Firstly, I think it worked because it had nothing to do with appropriation and was completely original in its conception and making. The two figures exemplify my work and the materials I use. Secondly, I think it struck a chord because it is very significantly addressing militarism which is something that is hardly ever addressed in the contemporary art world. You can talk about identity, gender and sexuality but you can never discuss militarism which in fact is what negatively affects much of the world population.

IN__I agree. I think that is because of the art market. Aspects of identity - like gender, sexuality and so on can be commodified and give the impression of change. But it’s largely just optics. Do you think making work about militarism is too raw and on the nose for gallerists and collectors to stomach?

HB__I think it is too present.

IN__The title We Come in Peace is a direct reference to the 1951 science fiction film The Day the Earth Stood Still by Robert Wise. Science fiction is a reference that runs through a lot of your work; your figures appear genderless, semi-human and “other” - not of our world. In a 2016 interview with Flash Art you stated: “I’m interested in a suicide of the self when I make the work: no country, no gender, etc. I don't want the work to be tied to any one specific self or ideology. When you are nothing, you can become everything.” Does science fiction offer you a means of removing yourself from the work while keeping the energy and idiosyncrasies of each sculptural “character” intact?

HB__Yes - science fiction allows me to express myself, be imaginative and deal with specific issues without becoming boring or didactic.

IN__What are some of your favourite science fiction movies?

HB__I watch all kinds of films that in different ways influence me; Alien (1979), Terminator (1980), The Thing (1982), From Beyond (1986), Ninth Gate (1999), Mask of Dimitrios (1944), First Blood (1982) just to mention a few.