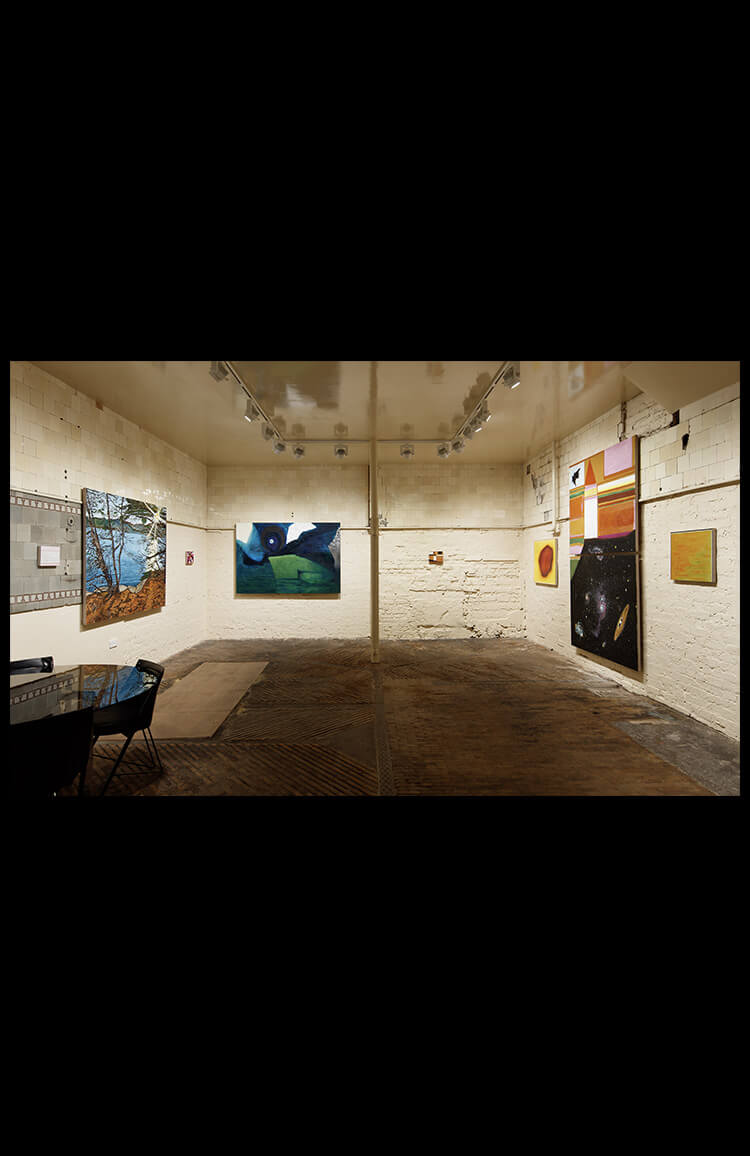

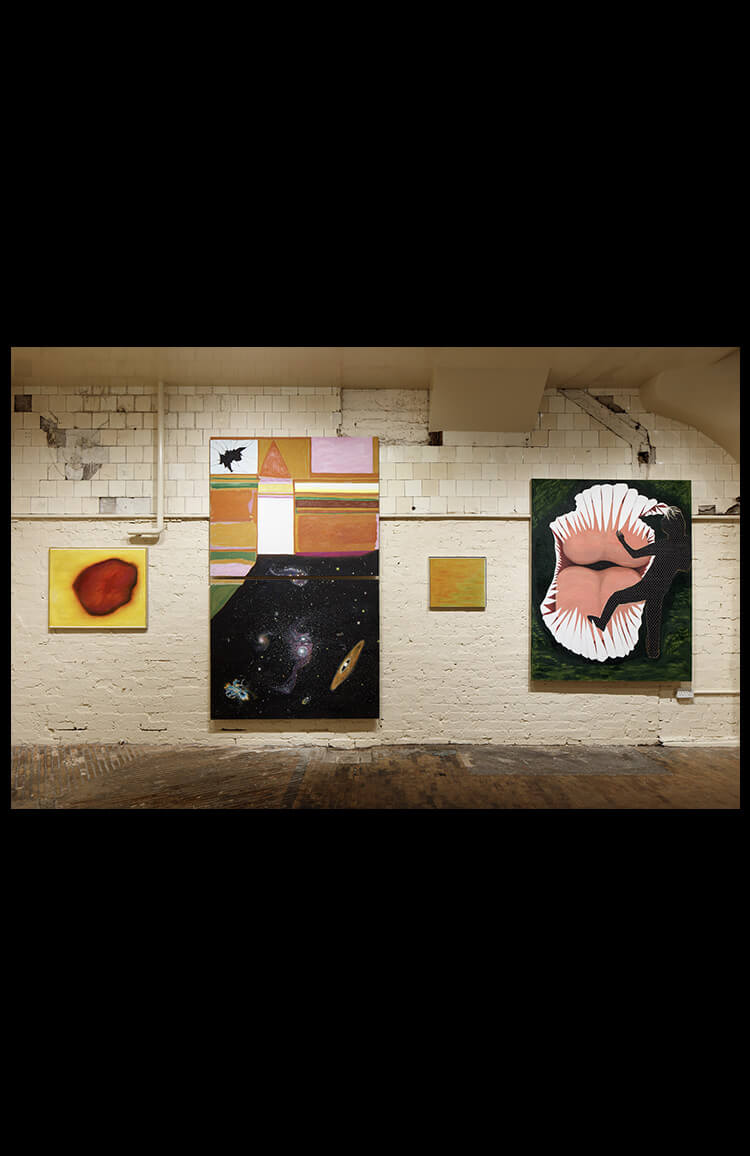

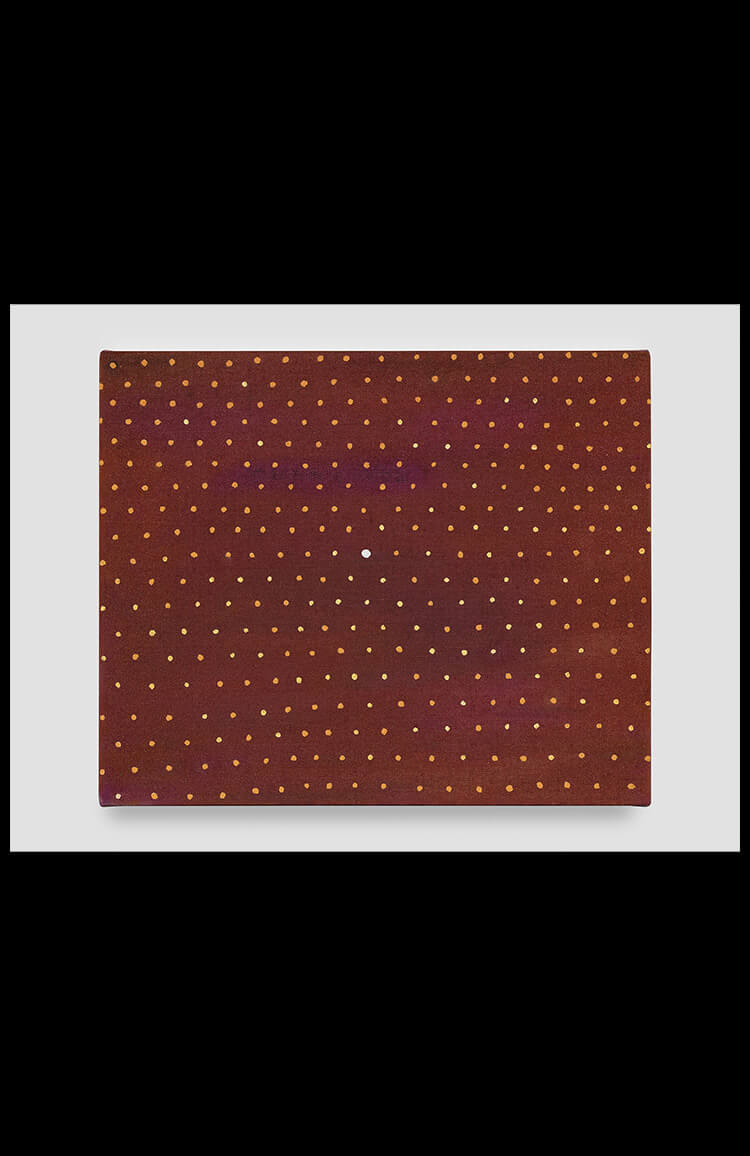

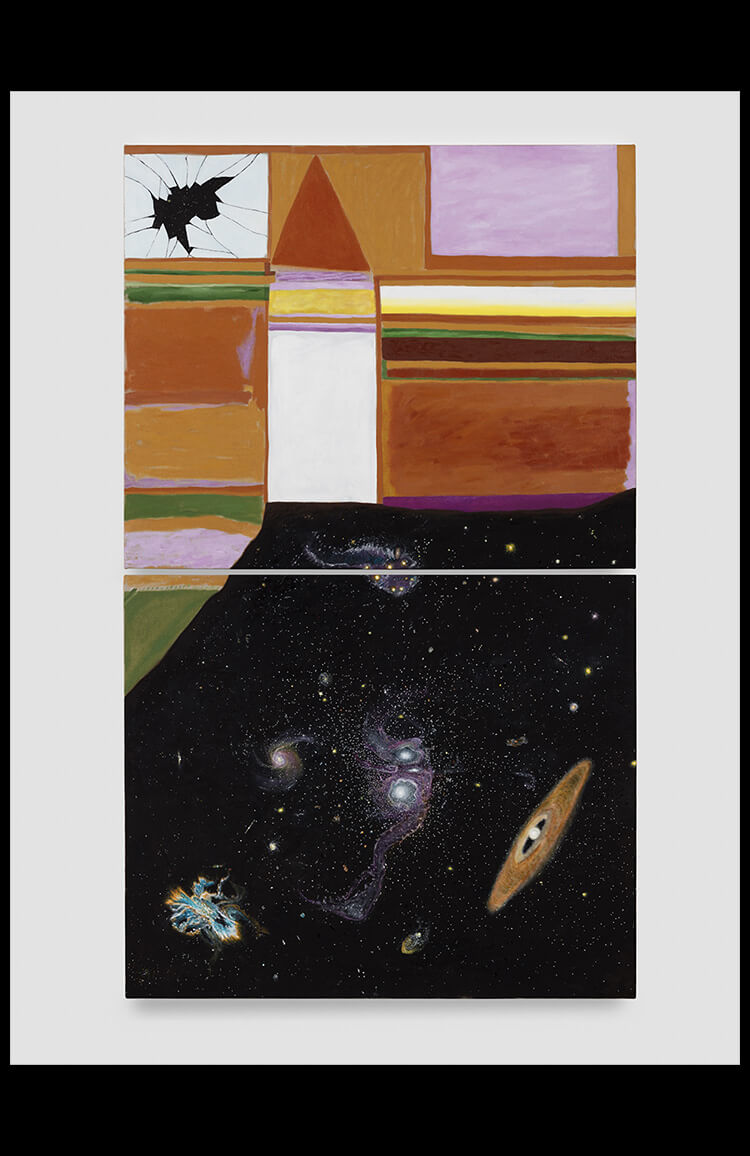

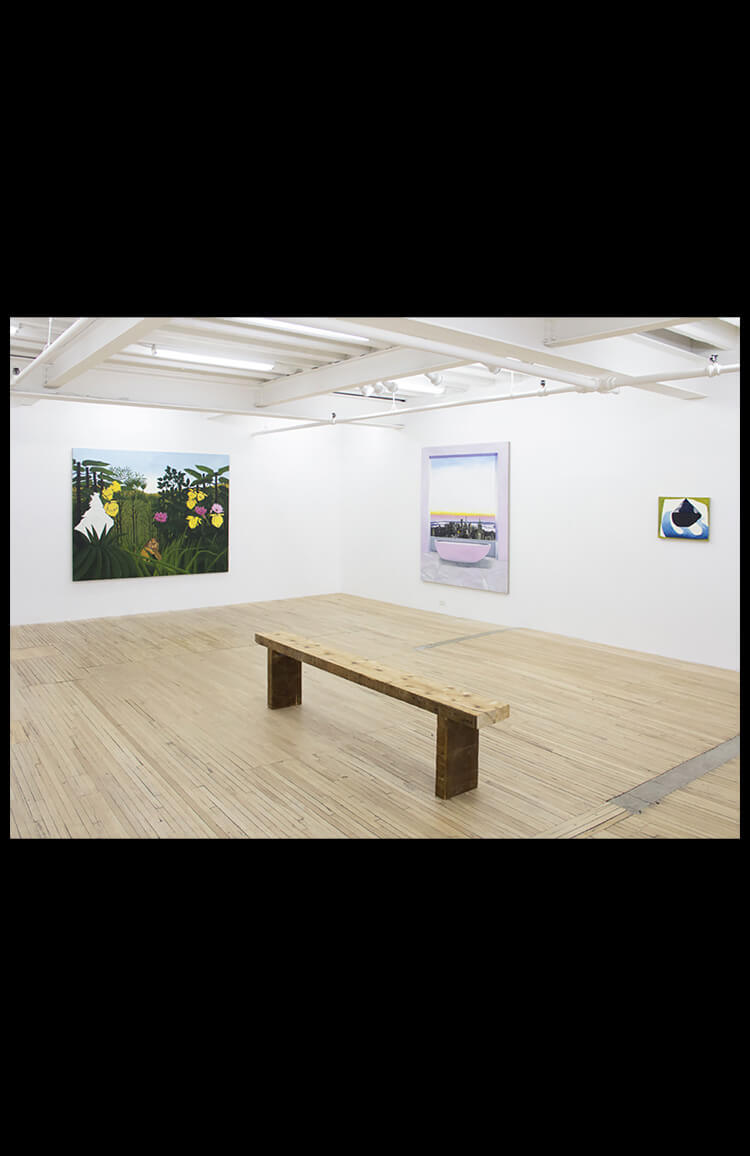

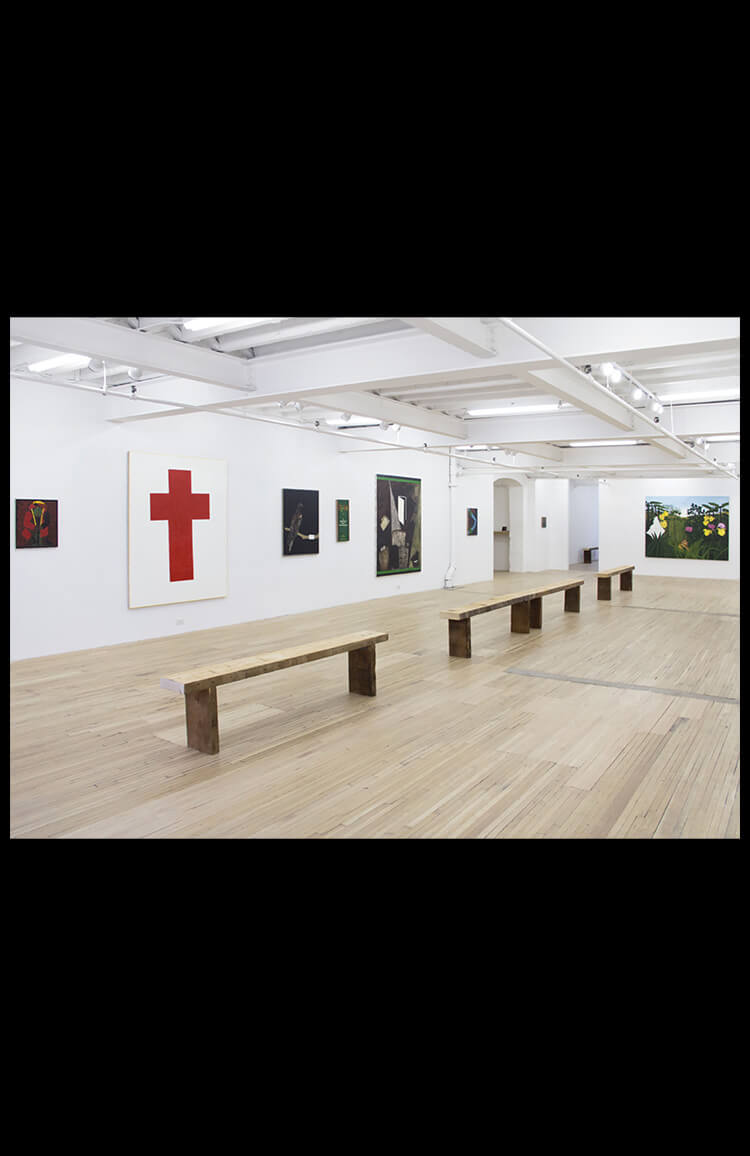

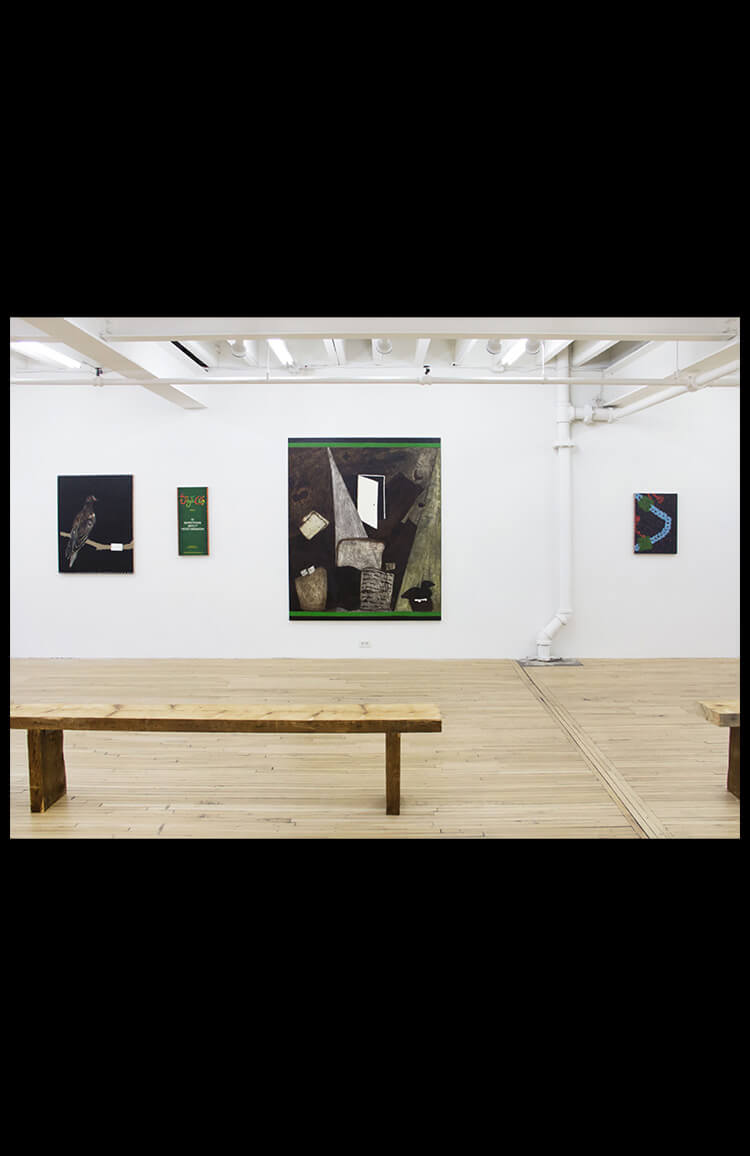

IN__I went to see your solo exhibition The Between is Ringing at Rodeo in London last summer. It was towards the end of a 6 month lockdown so it was really nice to finally see work in the flesh again. These paintings are a little different to some of your others in that most of them appear to be imagined scenes - they don’t seem to have a definite source or to be based on found imagery like much of your other work. Can you talk about the works you included in this show and how you made them?

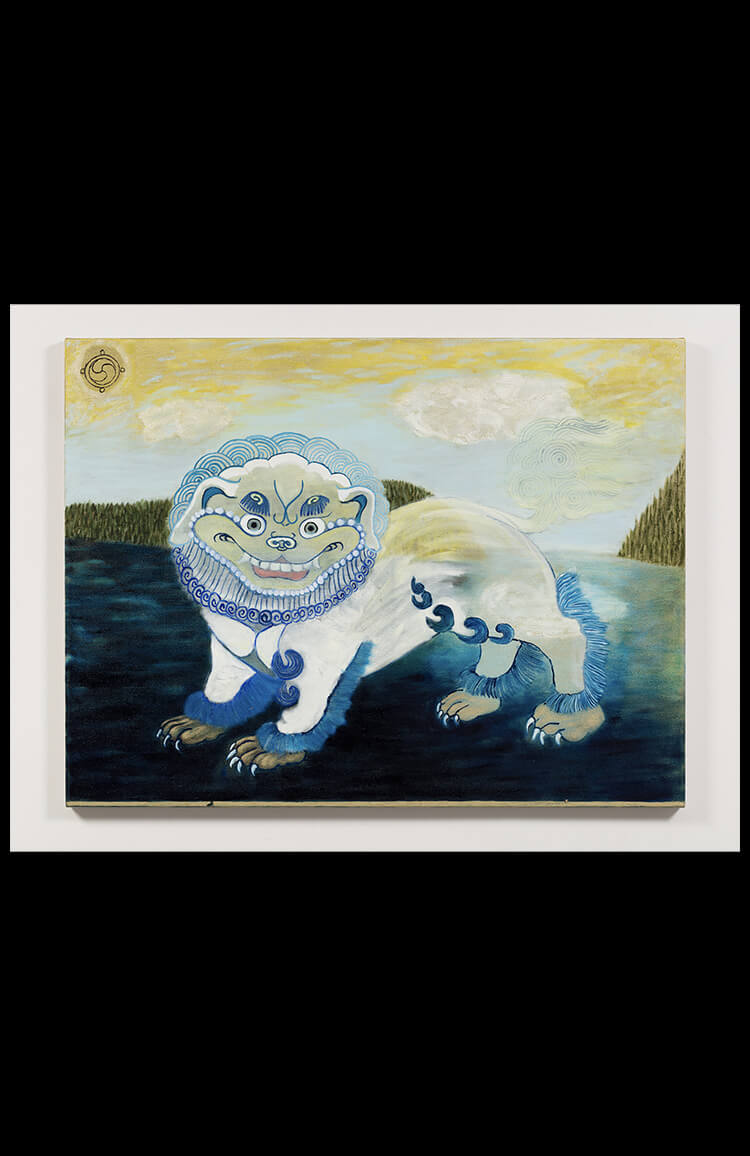

LC__Honestly it’s hard to get into it right now. I had so much fun making that show. The world was in lockdown and I didn’t really feel like starting with specific images collected from it. So most of them originated in abstraction from my head and then emerged as the Legend of Milarepa and a crazy way of relating to outer space. Because of the restraint put on our daily lives we had to create new relationships within our own minds. There was no way to plan anything for the future which was very shocking. It felt like emotional whiplash into the present moment over and over. I wanted to make paintings that reflected this new collectiver reality.

IN__A lot of these paintings are quite suggestive of celestial bodies. Are you into astrology?

LC__I don’t think I’ve ever made a painting about astrology but I’m interested in how in the past astronomy and astrology were one thing.

IN__Do you ever think about the reaction you want people to have to your work?

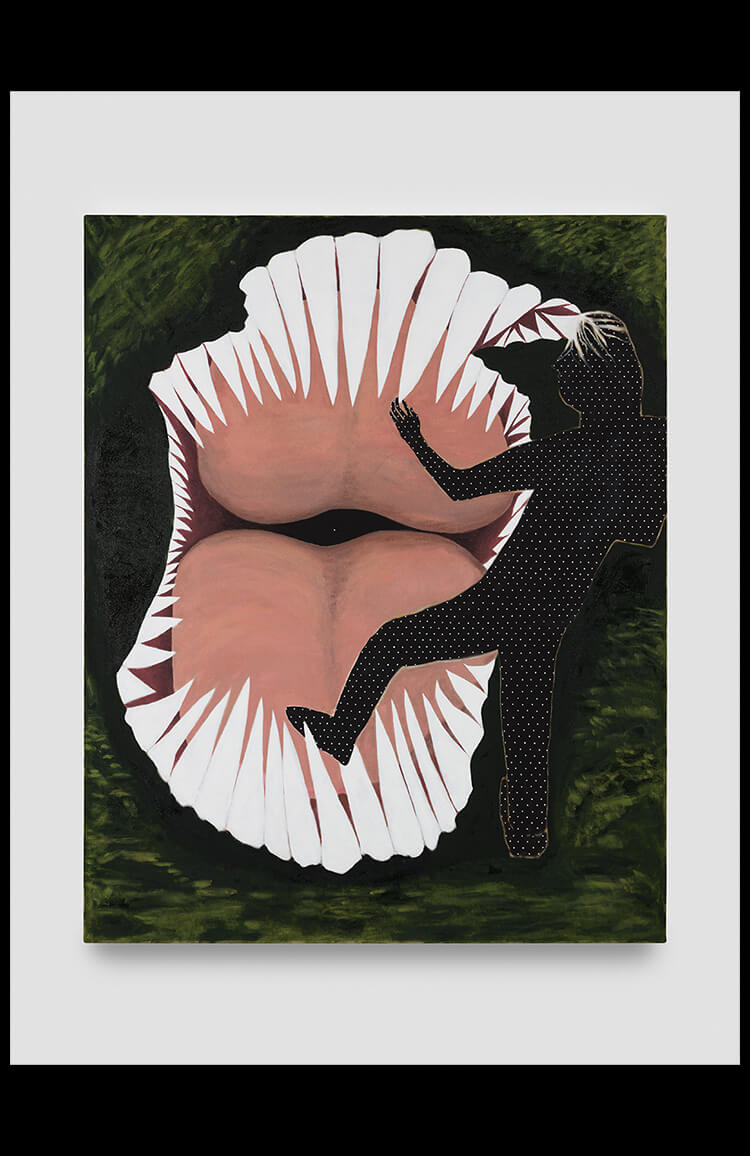

LC__I love it when there’s a lightness to the work; I want it to look really easy and free. I think I apply a lot of skill to my paintings but I only apply what’s needed in that moment and nothing more. If there’s something grand in the painting it’s for the pure joy of grandiosity; it’s not to show you that I’m some kind of master painter. I can relate this to meditation. It takes focus. It’s an easy thing that’s even easier to make difficult. I think painting’s the same way. Even when painting’s serious it should move through you like a thought.

IN__In an interview with Phaidon Press in 2016 you state that it was after studying Dada (the art movement) at college that you started making art “extremely furiously.” What was it about Dadaism that affected you so greatly and how did your work change as a result?

LC__I found it very exciting because it was all about smashing expectations of what it means to connect and communicate. It was not about perfection at all. Learning about Dada dared me to step into art as a frame of mind.

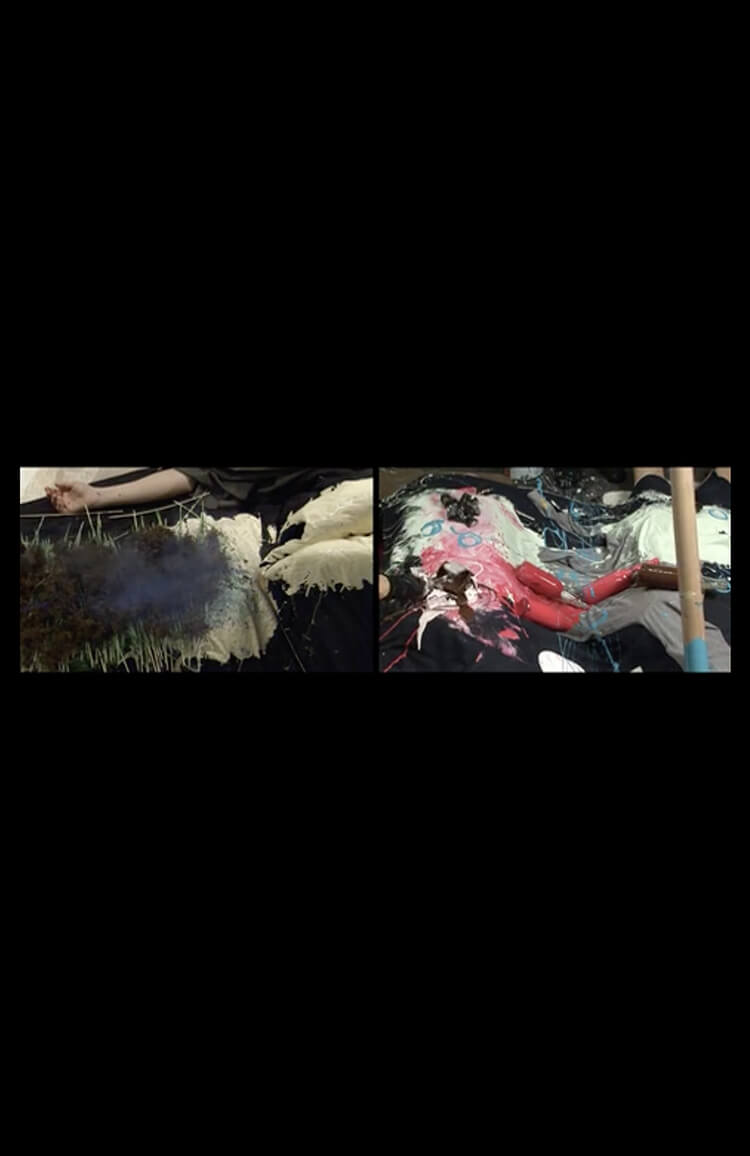

IN__You’ve also made video works. The Dada influence can be seen explicitly in a video series Painting Treatments (2010). Filmed in a studio setting and starting always with naked bodies partially covered with a blanket, random materials are dropped on this makeshift “canvas” like layers of paint; potatoes, dirt, actual paint, flour, clothing, tree branches, planks of wood… To me this video series performs what you do in your paintings in a manner that is exaggerated and ridiculous. In your paintings, as well as in these video works, everything seems to be the equivalent to everything else;

There seems to be a gleeful enjoyment of using things in the wrong way. Would you say that’s accurate?

LC__Yes. I really felt like everything was doing the painting in those videos. It’s hard to encapsulate it.

IN__A lot of Dada activities were very reactionary. Do you feel that your work is reacting against anything? Yours doesn’t strike me as a practice that reacts against things necessarily, but flows with them….

LC__If I was reacting against anything it would be the entire mindset of global capitalist culture in its full throttled attempt to disregard reality.

IN__What do you mean by “reality”?

LC__I feel we are living in a reality where we’re treating the earth, our minds and our bodies as though everything is permanent. What we’re taught is how to figure out who you are, how to be a strong individualist, create capital, and become eternal. This is the complete opposite to Buddhist thought which is to recognize our interdependence and aspire to compassion. To breathe, give our love to others, let go, and die.