IN__How involved were you with the subcultures shown in Fiorucci?

ML__Some of them very much so. I was a scally, I was a raver… I went through phases but it began with soul music for me. I was a soul boy when I left school. The Northern Soul movement was actually the generation before me but they were still around. I was still aware of people like that.

IN__In a 2016 promotional video you made for the Tate you described the feeling of growing up in Ellesmere Port, just outside of Liverpool, as being like “standing on the edge of the dance floor watching everybody else having a good time”. That’s how I feel when I watch Fiorucci. It’s very angsty. It feels like being an awkward teenager at a club - you’re in the moment but simultaneously on the periphery because there’s this internal feeling that you don’t fully belong there.

ML__I think part of that comes from my lived experience of coming from a town that was not just on the periphery of things geographically, but also always looking back on itself because its best years were already over. I set out with Fiorucci to make a subjective documentary about subculture that, as I mentioned, I felt were neglected. In the process of editing the video, however, I became more aware of its aura - it put me in this strange state of wanting to be inside the footage itself. At the same time, I felt very distant from it because I was always being propelled back outwards. So Fiorucci to me is a push-and-pull between this compulsion I had to be there - to be intimate and present with this archival footage, while simultaneously being aware that… it’s gone. They are ghosts. It’s a record that’s already fading fast. For example, the raver footage I included at the end is from 1993 and I made Fiorucci in around 1998. That’s just five years later, but already that ghostly feeling was there for me.

IN__I get a melancholic feeling of aspiration from Fiorucci. A lot of the groups shown in the film, for example “scallys”, were made up of mostly working-class kids who wore branded leisurewear and sportswear as a way of “blending in” with the middle-class. In this way they were using certain brands as a form of aspirational drag to give the appearance of moving up a class, even though their economic situation remained the same. I am reminded of Jennie Livingstone’s documentary film Paris is Burning (1990) which chronicles the underground ball culture of New York City. Many of these ball categories were also concerned with blending in or “passing”, with trophies being awarded to the queen who could most convincingly dress and act out conventional cisgender, straight, white roles such as “executive”, “school girl” and “military soldier.” Was that an influence on you?

ML__Yes, big time. Very much so…

IN__…I wonder then how you feel about some of the criticism Fiorucci has received in terms of its subject matter. In a 2016 artnet review of your MoMa PS1 exhibition of that year, the writer Christian Viveros-Fauné wrote of Fiorucci and its dancers: “subversive this film is not, unless youth and drug culture is your idea of sticking it to the man.” While watching the video again last night on YouTube I noticed you’d left a comment underneath quoting him verbatim. Did you do this as a “fuck you” or were you agreeing with him?

ML__It was just me being stroppy I think *Laughs*

IN__*Laughs* What do you think about what he said though?

ML__Well, I think he might be right. That’s probably why it got to me and why I put it up. Fiorucci is about consumption and about how subcultures were subverting the consumer culture of the late 20th century. It was about the brand loyalty some groups had and the records they purchased; the way you consumed and how you could disrupt that in some way. Then there was this Frankfurt - Adorno school that said there was nothing ever subversive in it. That it was completely delusional…

IN__I guess you could say it’s delusional because you’re centering your whole self concept around consumption - the things you wear, listen to and consume define your personality.

ML__Yeah, that’s the argument! *Laughs* But I still want to respond to that by saying something as banal as: “But it didn’t feel like that!” because it was to do with feeling. Even if that feeling was delusional, it was powerful.

Fiorucci is essentially about working class youth who, through consumption, produce their own culture and their own vital communities. So there was a form of aspirational drag going on, like you mentioned, but it’s actually productive in that sense. It’s not just delusion. That to me outweighs the critique that they’re engaged in just another delusional form of capitalism because it establishes these networks, these communities that not only thrive but also produce an energy that can extend out to create other social relationships.

IN__Do you think those groups were doing anything subversive?

ML__No, I think it just establishes a kind of difference. I’m not really interested in whether it’s subversive. It’s a means of creativity, specifically, it’s a means of creating a culture that is owned by you. It’s the ownership that’s important for me. It’s a territory that’s yours and that’s been determined by you. Going back to class, it’s important because it hasn’t been trickled down, it bubbles up from below. It’s coming upwards from you and that makes those bonds very strong and powerful. That’s what I find remarkable about it. Not that it’s subversive. I don’t think it upsets any balance particularly…

I think those subcultures of the late 20th century operated outside of the mainstream because the mainstream was so clearly defined. You could point to its institutions and say “this is the hegemony” and operate outside of it and, I suppose, be subversive to the mainstream in that way. But the mainstream itself is being disrupted now, right? Liberal institutions and mainstream media are being assailed on all sides…

IN__I think the internet has a lot to do with that. Pre-internet, I feel people would identify themselves more geographically; the kind of music you listened to and the clothes you wore would usually be an indication of where you grew up and who you hung out with. You had pockets of “local” culture. Now people absorb culture through the internet and it’s more common to have these experiences on your own, through a screen, so you’re distanced from the beginning. Perhaps this makes it harder to form distinct groups around music or fashion in the same way as before.

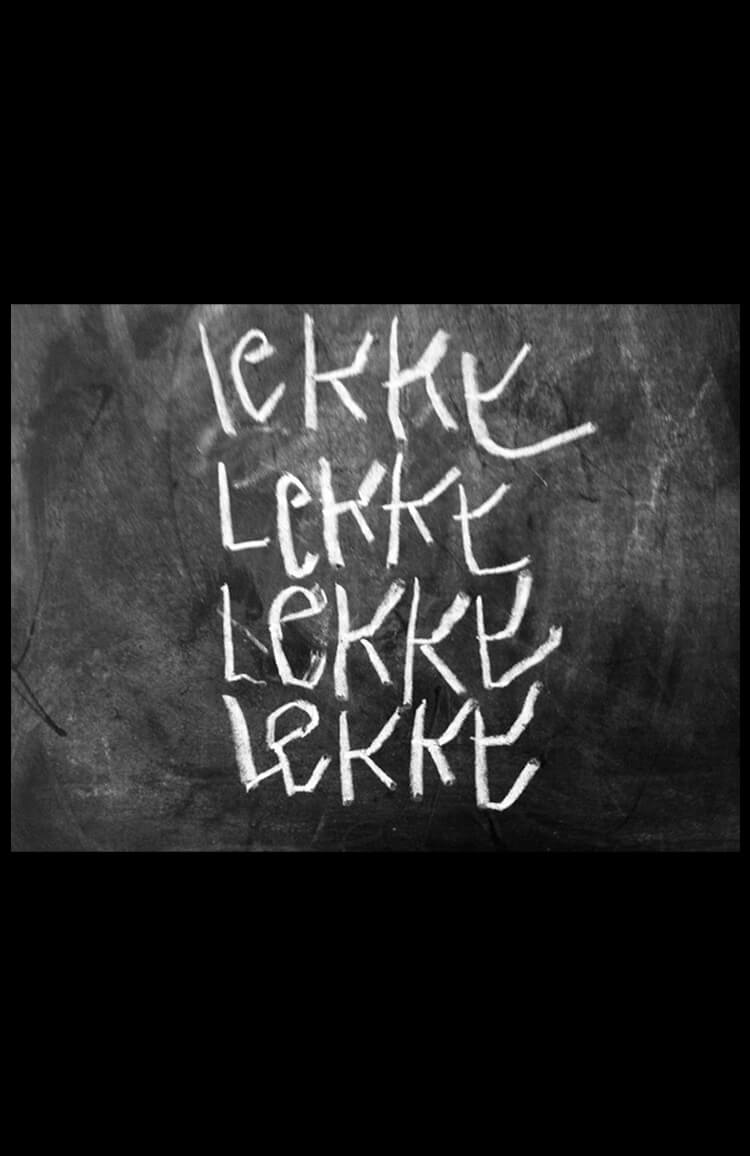

ML__Yeah, it’s very different now. It’s not that subcultures have waned it’s that the internet has extended itself into all of these areas that made a subculture able to thrive, not just in terms of fashion, but also the record industry and the ubiquitousness of brands. Part of what Fiorucci is about is how each of the geographic regions that produced these different dance cultures happened in isolation. They’re basically weird phenomena that had been left unnoticed for a long period of time so they were able to mutate and branch off into all these other crazy phenomena. That can no longer happen after the internet because everything is immediately observed and absorbed. Nothing has the time to do that. Subcultures are just one of the many things the internet has observed and defanged.

I’ve just read the book Neon Screams by Kit Mackintosh and it’s about how autotune has mutated over the past fifteen years. He mentions music artists who use autotune like Young Thug and Future and newer artists like SahBabii and Baby Keem. For me, when I first listened to their music I thought: “This is what I thought the music of the future would sound like.”

IN__You mean when you first listened to Future you thought “Oh yeah, he really is the future”?

ML__*Laughs* More Young Thug than Future. When I listened to Young Thug I was just like, “what the fuck?” It’s so new. There’s no sound that existed like that previously.

IN__Do you mean specifically the way he uses autotune?

ML__Well in Neon Screams Mackintosh was talking about how these artists are making music that is emotional and psychedelic, but it’s all channeled through technology, which produces a very strange effect. It’s essentially the realisation that, by making yourself into a cyborg, you can be more human.

IN__Yeah, it’s a way of protecting yourself. You can be more vulnerable and open about uncomfortable things because this protection, this distance, is already baked into it. It’s you saying it but it’s not your voice. It’s like wearing a mask.

ML__Exactly, yeah. What fascinates me about the relationship between distance and intimacy I mentioned before when we were talking about Fiorucci is that I think it’s a part of the contemporary condition because everything is mediated now. You’re always trying to get closer to something or wanting to feel something while being in this alienated, mediated state. You have to find your own complicated dance or relationship with things in order to induce some kind of aliveness. You have to go to something quite cold and mechanical in order to feel more human.

IN__Is that why a lot of your work hasn’t featured yourself directly? For example, in Fiorucci, it’s all found footage, but it’s a stand in for a personal experience you had…did that allow you to be more vulnerable?

ML__Yeah, exactly. Because they’re like surrogates, right? Usually I find some kind of surrogate body that I can inhabit and then feel “present” within that.

IN__There’s a tendency for the art world to fetishise people who are considered “other” in some way, whether that’s because of your class or your gender and so on… Did you feel you had to fetishise yourself or your position, having a working-class background, in that way? Because I feel like it’s implicit to the art world that if you want to make any money from your work you have to play into that a little bit.

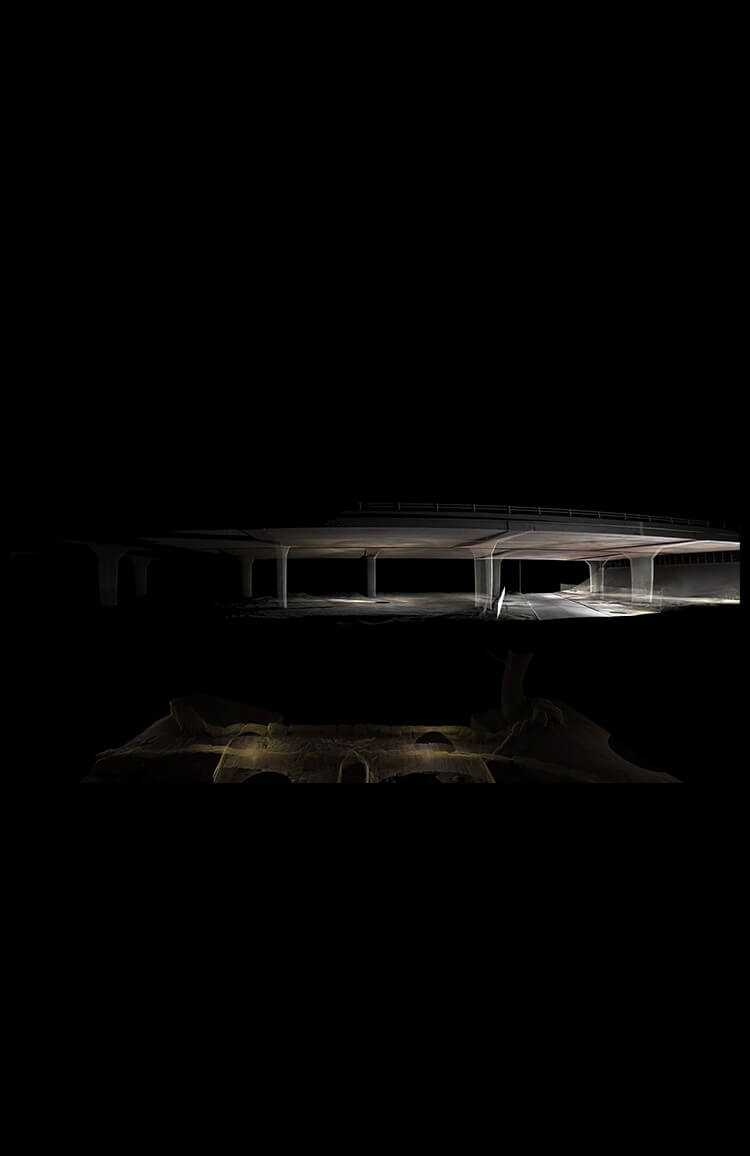

ML__Did you see my show ‘O' Magic Power of Bleakness’ at the Tate I did in 2019? With the motorway bridge?

IN__Yes…

ML__That show was an attempt to address those issues for myself.

IN__How?

ML__Well, I had a supernatural experience when I was younger that I’d forgotten about for a long time. I have two small children now and the older one has started getting into fairies and magic so I’ve been watching a lot of these shows with her… and it resurfaced a lot of memories of this past encounter. I couldn’t grasp the reality of the experience or which realm it took place in, so I started reading about folklore and changelings and how the fairy realm interacts with the non-magic realm. In these stories they snatch up youths at the point at which the fairy kingdom needs to revitalise itself by mixing its bloodline with human energy. It was a metaphor for my own experience. I felt like I was a changeling in that, when I returned home, I felt as though I’d been transformed. I was no longer able to converse with people I’d grown up with, or my family. I felt alienated from them.

‘O' Magic Power of Bleakness’ is about these two events: the supernatural encounter I had when I was young and the experience I had as an adult of becoming transformed and alienated through language. The piece follows the story of a bunch of kids under a motorway bridge and one of them is talking about how he wants to escape the town they live in. He’s aspirational. I was trying to collide a classic, socially conscious youth film with a fairy story. In every youth film you watch there’s always one kid who wants to get out, right? Well, in my story, that kid gets snatched away to fairyland and a changeling returns in their place. It then follows the other kids trying to understand what happened to their friend. It’s a magical realist autobiography.