IN__You’ve mentioned in other interviews that Sigmar Polke is a big hero of yours…

CM__Yes, I seem to remember from what I’ve seen of your work that he might be a big hero of yours too. Is that true?

IN__Yes, I love Polke. He really opened up a whole world of possibilities for painters and I think it’s interesting to see how the artists he inspired took them down very different routes. What was it like seeing his work for the first time?

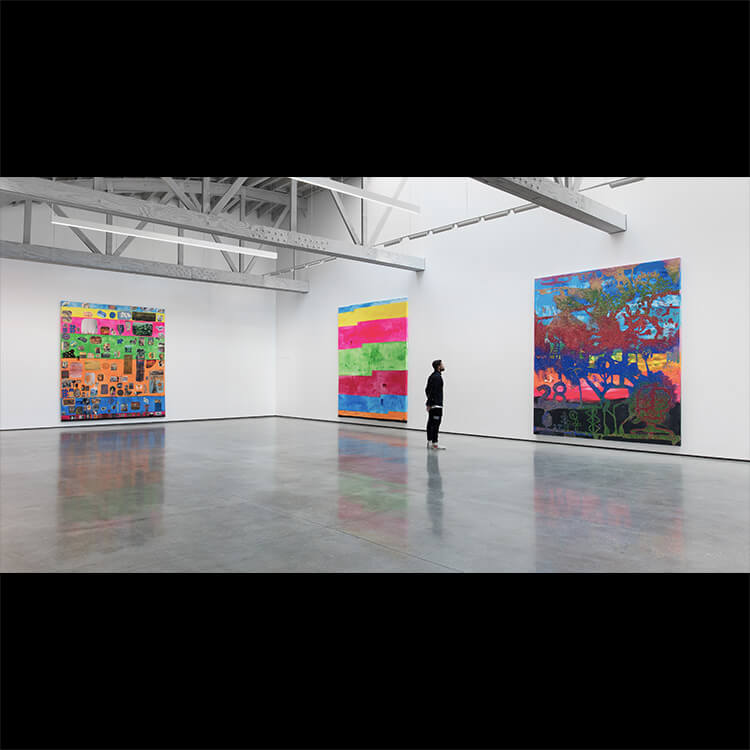

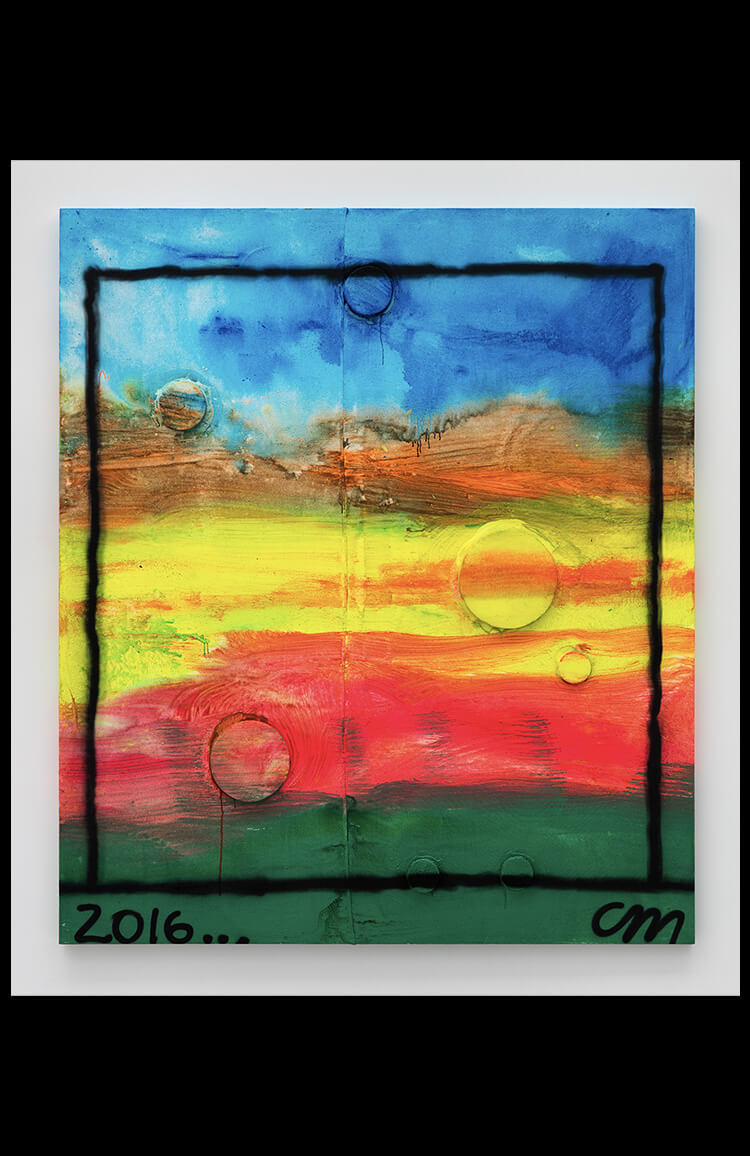

CM__Polke was a revelation to me… when I first saw that work it was a huge shock! He found the freedom to do abstract and figurative work side by side… that was unheard of in New York. In New York you really chose which side of art history you were on. Of course, that all seems so quaint now.

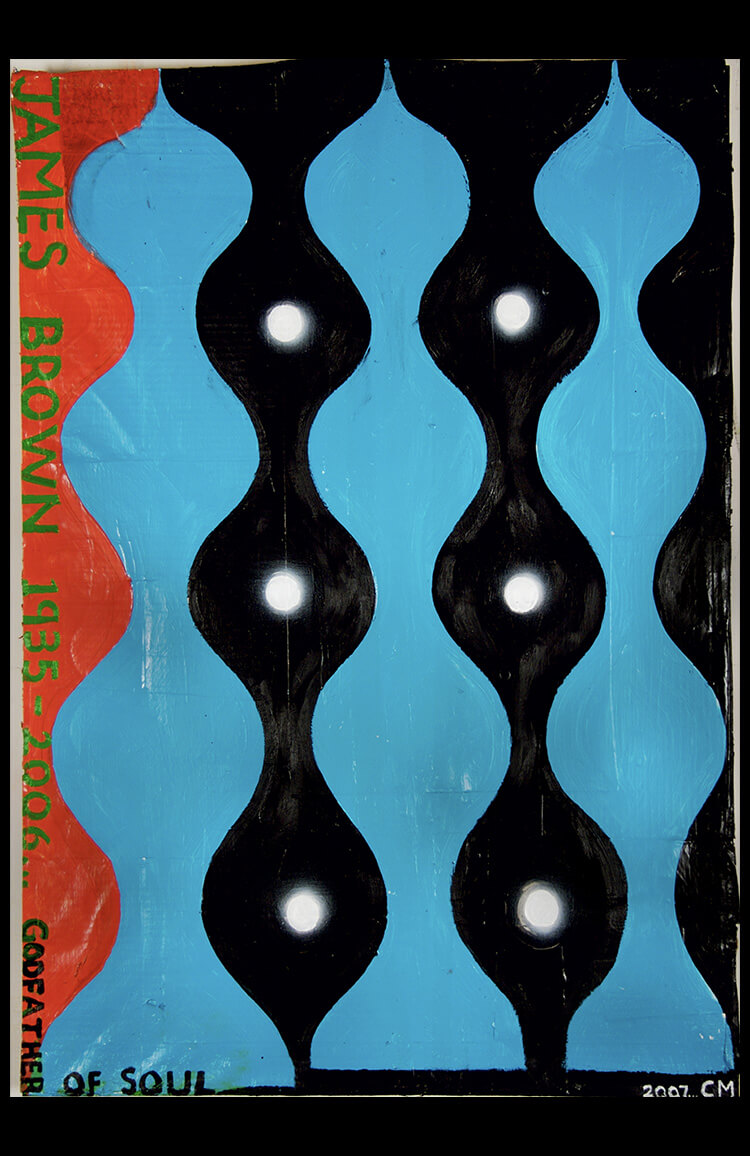

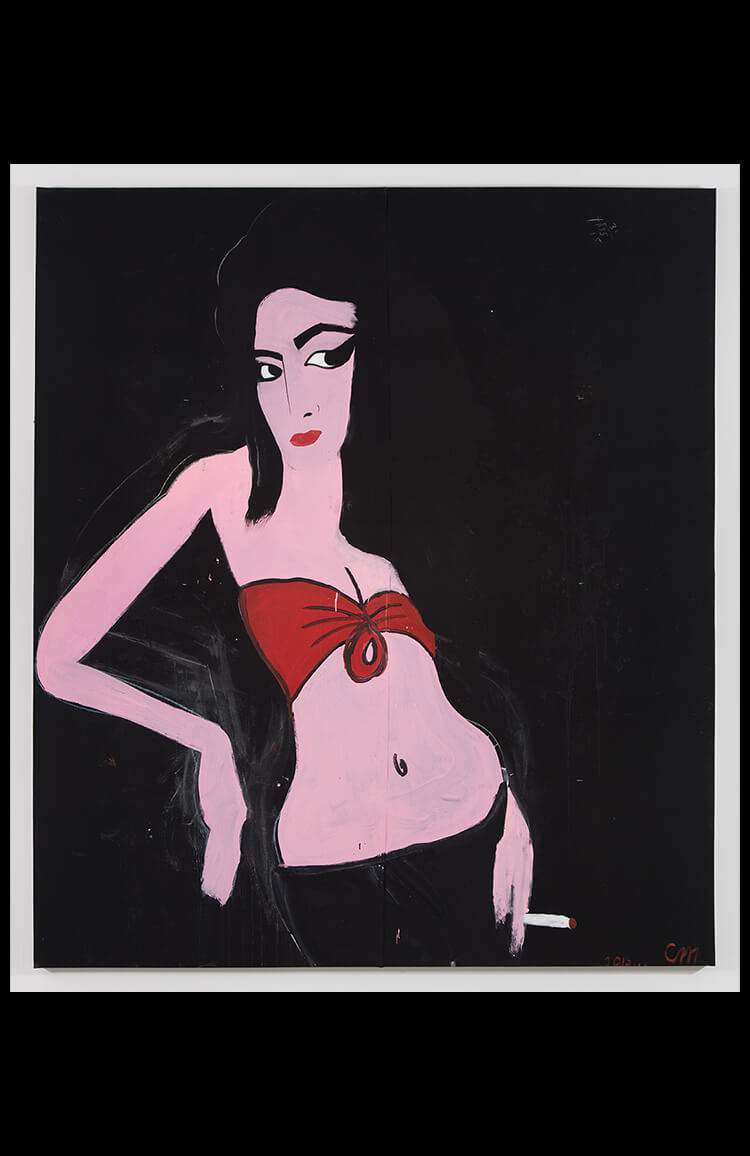

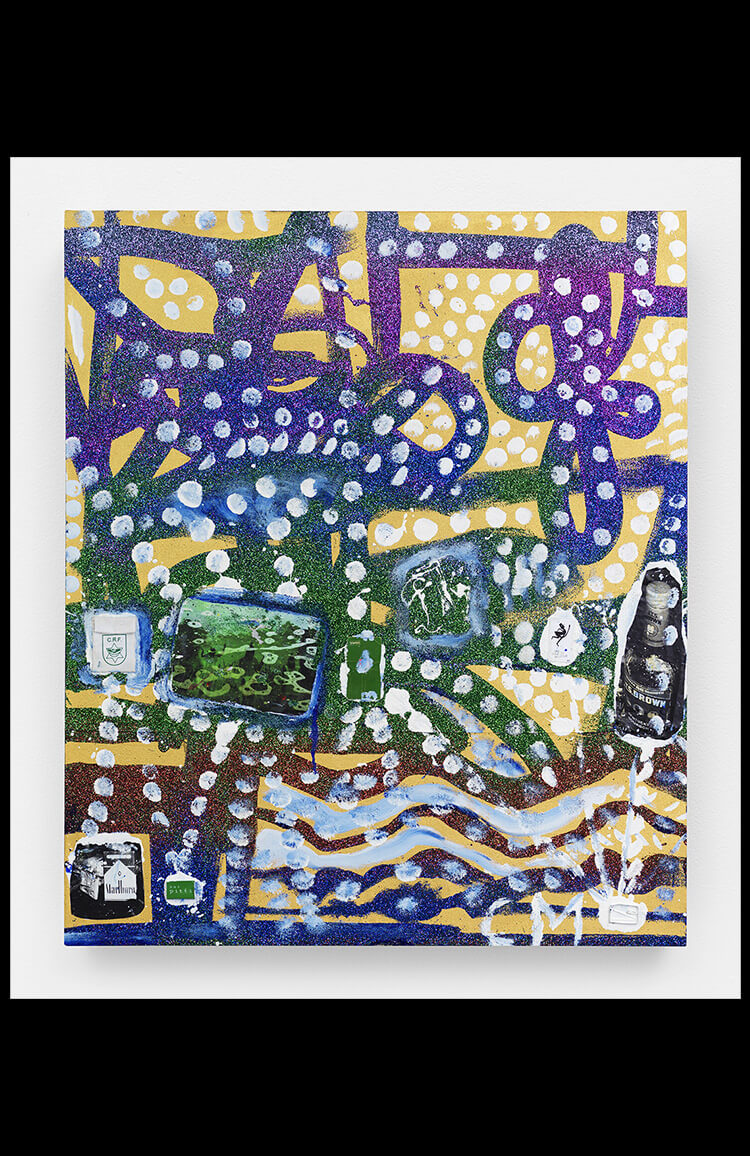

When I first saw a group of his paintings I thought “here is a man that is accessing the whole grand tradition of European painting.” He could paint about history, he could paint about eroticism, he could make funny paintings and he could also make serious Holocaust paintings. He was able to access psychedelics and all of his various interests in a very direct way.

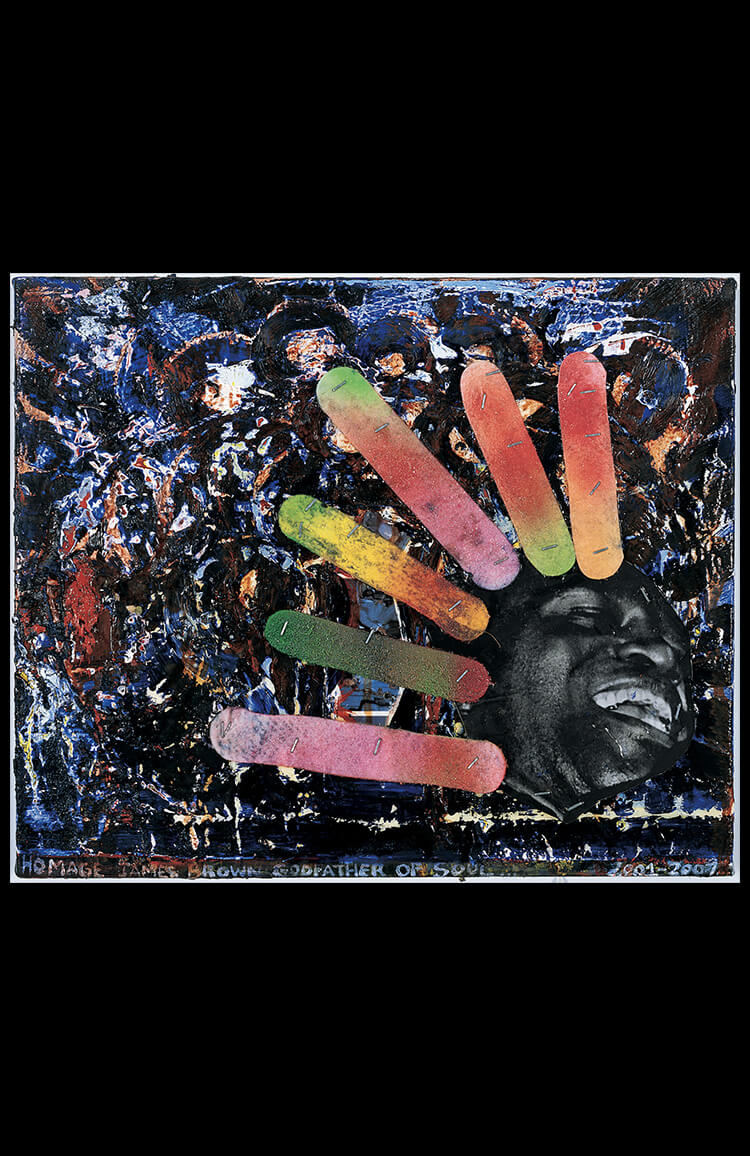

Jean-Michel Basquiat was also a huge influence. I knew him right at the beginning. Again, here was somebody who could bring whatever he was thinking about, whatever music he was listening to and it all went in to his work. He would read a book and then he would just start writing in his paintings. That was such a freedom at the time for a lot of us. I had personally been struggling with the problem of how to fit my work into these very narrow categories. I was making very odd drawings at the time but I had felt up to this point that they couldn’t really be a part of my work, so seeing these shows taught me a lot.

IN__It took a while for people to start showing your work, didn’t it?

CM__Yes it did. I was around 50 when I started making a living from my paintings.

IN__Did you find it difficult?

CM__I have no regrets but there were times when it was hard. I went back to college as an adult because I needed to get a job to support myself and my kids. I didn’t want to do menial jobs anymore, I wanted a meaningful job. So I went to the School of Visual Arts in New York City to study art therapy. When I was younger I thought the worst thing that could happen to me was to work full time - it felt like an admission of real failure as an artist. In reality it turned out to be a great thing because, through my work as an art therapist I learned so much and met the most amazing people. It changed my attitude to my work.

IN__What led you to art therapy?

CM__When I was young I learned a lot about Jungian archetypal psychology - I was interested in the idea that art could access certain archetypes and emotional states that would bring healing- first for the artist and then for the culture because you were providing people a mirror that could help people accept themselves and feel the truth of things. My best friend Peter Acheson, who is a terrific painter, was also very involved in Jungian therapy. That’s also what I took from Beuys - that he made his work to heal himself and then he offered it up to society to suggest a possibility of healing and connection.

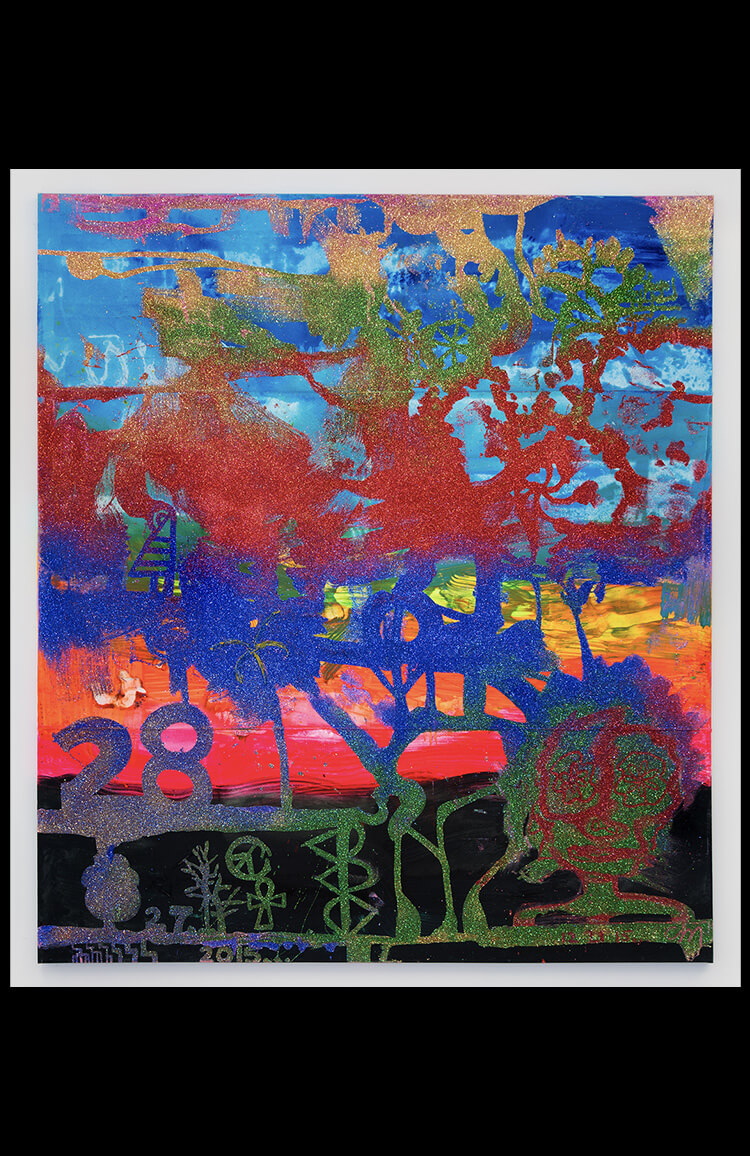

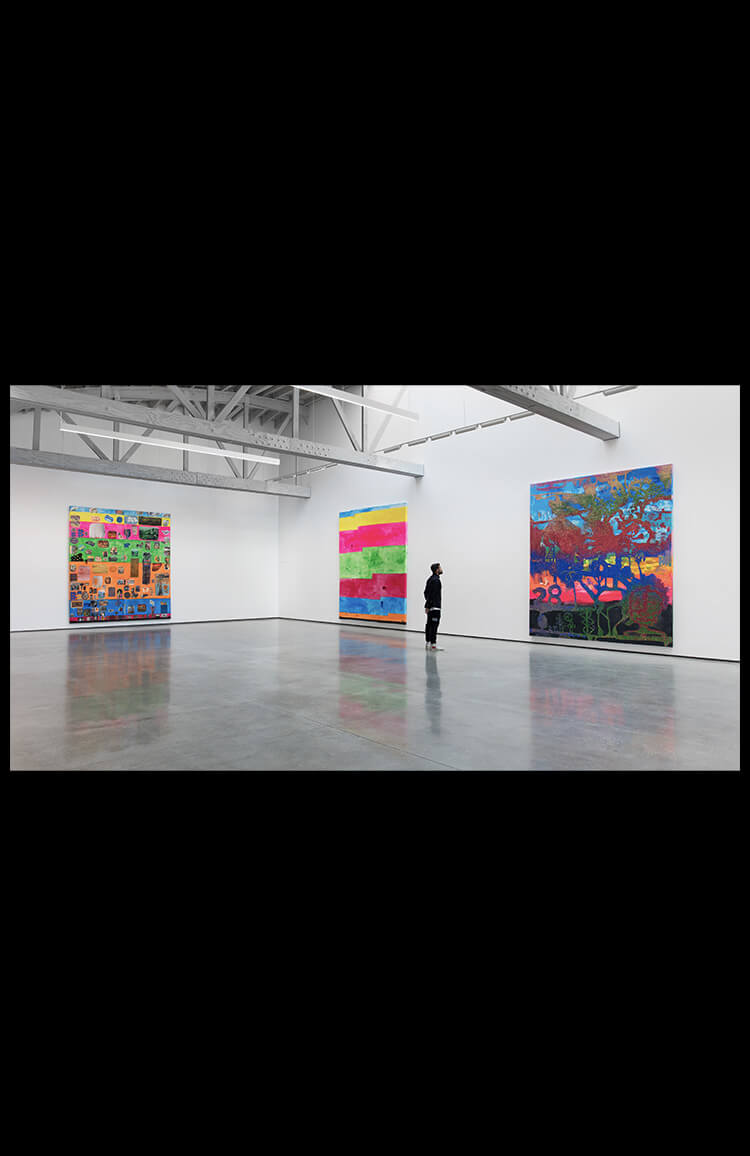

A lot of my friends were dying of AIDS and I started working as an art therapist at the very beginning of the AIDs pandemic. I worked in day treatment settings and in hospital and nursing home-like settings. I worked with such a fascinating and profound group of people. A lot of the people I worked with had been heroin addicts and criminals and had the most terrible experiences in their lives. It was harder for me to go home after work and say “woe is me, I don’t have an art career” – I mean my children were healthy; they were growing and happy and I was not dying. I was not in prison. It certainly gave me perspective on my life and it changed my painting very much. I actually learned about glitter while working as an art therapist in Brooklyn - all the clients loved to use it and I quickly became a convert.

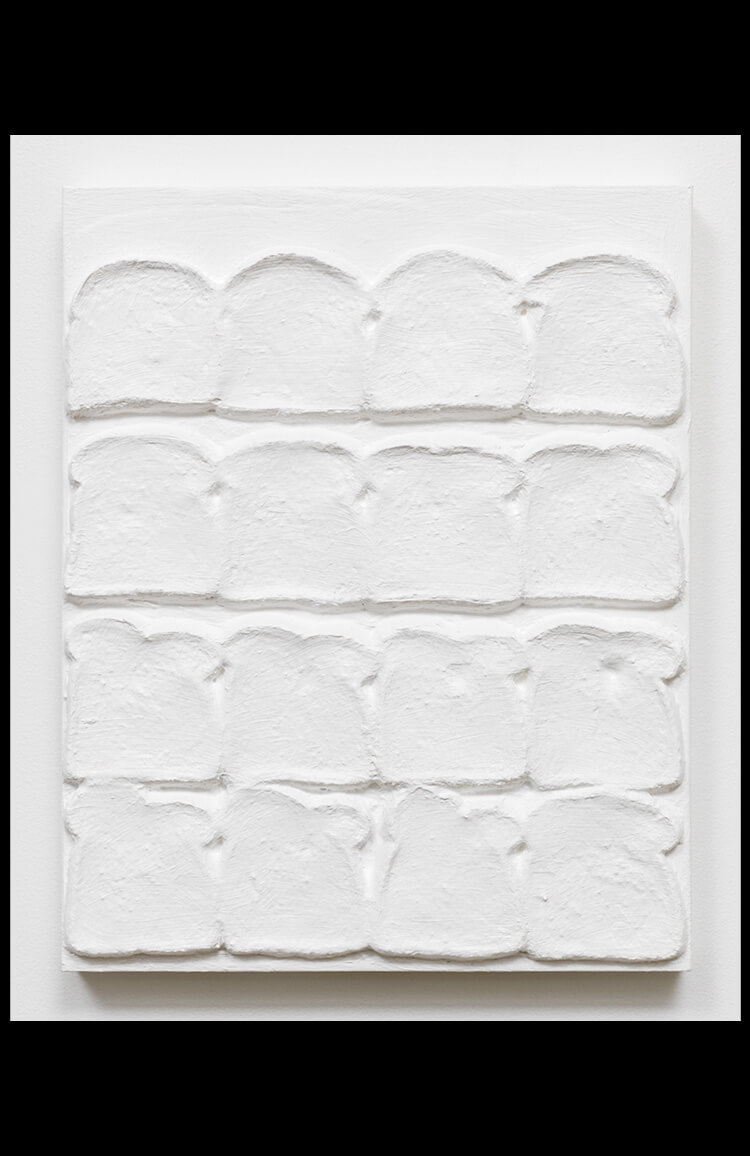

IN__It’s interesting to hear you talk about reaching this point of seeing your work, through Beuys and Jung, as this healing activity because when I look at your work I’m thinking about permission. More specifically, I’m thinking about the idea that you can give yourself permission to do things just because you want to and for that to be okay; following your instincts and allowing yourself to make things fun and enjoyable and for that to be okay too. Things don’t necessarily have to be difficult to make it valid and all work does not have to be hard work. I think a lot of people struggle with that.

CM__Well, thank you. I remember, many years ago, I asked the artist Richard Tuttle: “How does it feel to have been such an influence on so many people?” And he said exactly that : “when I was a young artist there were people who gave me permission to become myself - If I can do that for somebody else, that’s great.” I like the idea of permission very much.

IN__I think art schools can really get in the way of giving yourself permission because they’re geared towards verbal language; most of your time is spent trying to justify or defend your work. This can be very helpful in that it’s an exercise in learning to stand up for yourself, but it can become really toxic if it gets in the way of purely enjoying or accepting the things that you love - both in your own work and in the work of others. It’s easy to internalize this constant questioning of whether something is “good enough” for a very narrow audience.

CM__Right. It’s corrosive to think that one has to justify and control one’s work as an artist. I’ve done very little teaching but I noticed there was a feeling among the students that if something happened easily then it was an object of suspicion. It was better to struggle through something, even though you weren’t enjoying it, to prove you were working hard. Critical thinking has a very hard time dealing with pleasure…

IN__You started a painting undergraduate degree yourself at Yale in 1972, dropping out in 1975 to move to New York and be an artist. Did you drop out for some of the reasons we’ve just been discussing?

CM__Well the good side is that the graduate school was quite lively and, in those days, the graduate and undergraduate schools of painting were in the same building. That means that, even though I was an undergraduate, I could still go and hang out with all the graduate students and listen to their critiques. At the time anybody who was a serious artist was going to New York City and so all these graduate students were leaving to go there too… so I just thought, “Why wait?” And I went. I was about 20 years old at the time. I’m not a fan of art education.

Al Held was a teacher in the graduate school at that time and his minimal paintings from the 1960’s like ‘The Big X’ and ‘Ivan The Terrible’ totally shocked me. He had a retrospective at the Whitney museum that just blew me away. It was one of reasons I said “I’m dropping out of school, this is ridiculous!” Years later I would jokingly blame him and he’d go “Don’t put that on me!”

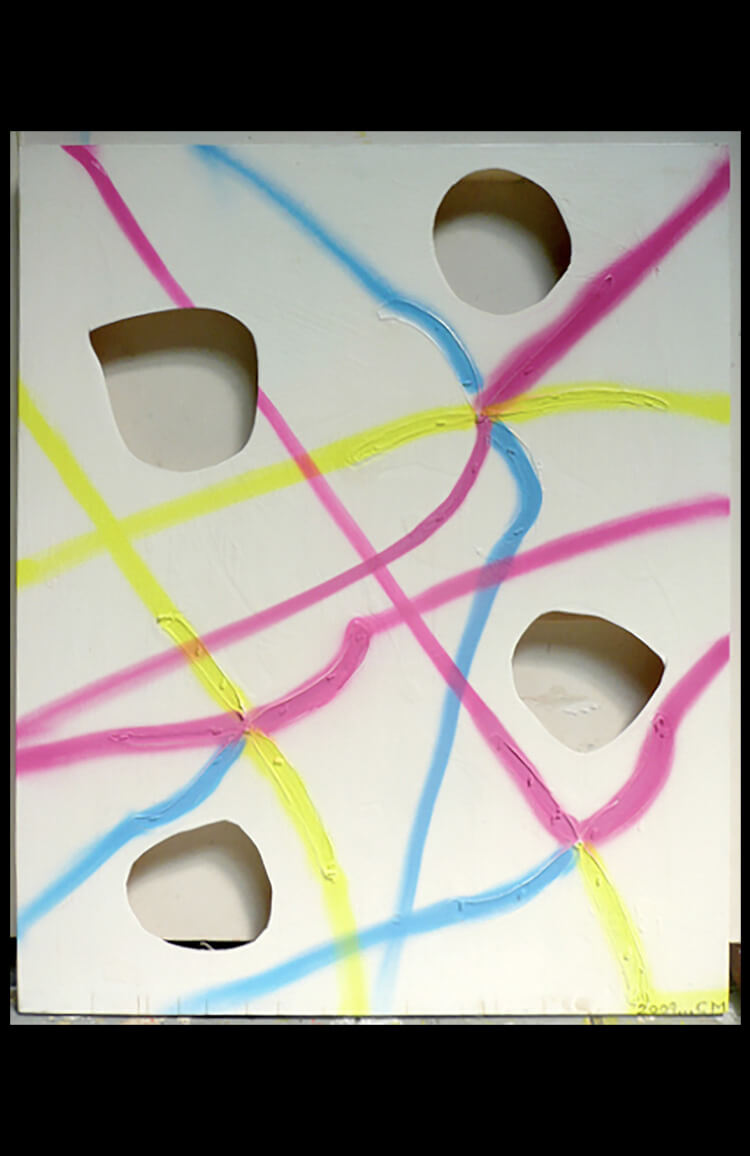

Anyway, as a younger painter you have these first loves in art that influence your painting. I felt as if those Al Held paintings were the paintings I had always wanted to make! So I tried to paint them. I also tried to paint like early Elizabeth Murray for a few years. And artists like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg also had a huge influence on me. It’s how you start - you try to do the things you love…

IN__I read that you went back to teach later on and set fire to a student’s work…

CM__I had a very interesting student at Bard. They were very unhappy with their work and often talked about wanting to destroy their paintings. My natural reaction in a situation like that is to encourage people and say “Come on, it’s not so bad, there’s something happening here! Make another one! Plunge in!” But after months of this I was just growing weary and asked the student “Okay, how would you like to destroy the work?" There was a fire pit in the yard outside of the school so we decided to set them on fire. At that point they really perked up so we started taking some works out to the fire pit and setting them on fire. Other students came up to us and asked what we were doing. When we told them we were burning paintings all the students were like “Oh, can I bring some of my paintings? Because I’d like to destroy some of my work too!” *Laughs* That was probably the peak of my teaching career.

IN__*Laughs* I think everyone sets fire to their work at least once.

CM__It’s a rite of passage. It’s important.

IN__Yes and it completely frees you up. When I start a new batch of paintings I usually write off the first painting as a “burner” painting because it takes the pressure off and helps me loosen up. You can just do it without worrying too much because you’ve already written it off in your mind.

CM__Exactly! Well by the end of that afternoon we had the whole class sitting around this big bonfire and people started saying “Why don’t we make new things to burn?” Since they knew they were going to burn it, like you say, they started making the most wonderful paintings and drawings and then people would go: “Oh but that’s a great one!” And then the whole class went: “No you have to burn it! You have to burn it!” *Laughs* Knowing that you’re going to destroy something takes the pressure off and allows you to just be there. There’s a great lesson in that. Do you teach?

IN__Yeah, I teach art and photography to high functioning autistic teenagers…

CM__I bet there are some fantastic painters among them.

IN__Yeah, it’s nice teaching art in that context because, even though it’s being assessed, its most important value is functional. It’s something that’s meant to help you emotionally - you’re actually supposed to enjoy it.

CM__But I bet you’ve noticed some of the paintings are also terrific.

IN__Yes! I think it’s for that reason. Are there any rituals you do when you’re in the studio to free yourself up?

CM__Well, I live upstairs and my studio is downstairs so the big thing I do is just to go down there. That’s the discipline, but what’s nice is to go down without pressure - just to be there. So when I’m there I can take a nap, that’s a great way to get some work done, or I can do chores, stretch a canvas, mix up a bucket of paint, move something around… My wife and I have an expression where we say “I’m just puttering around.”