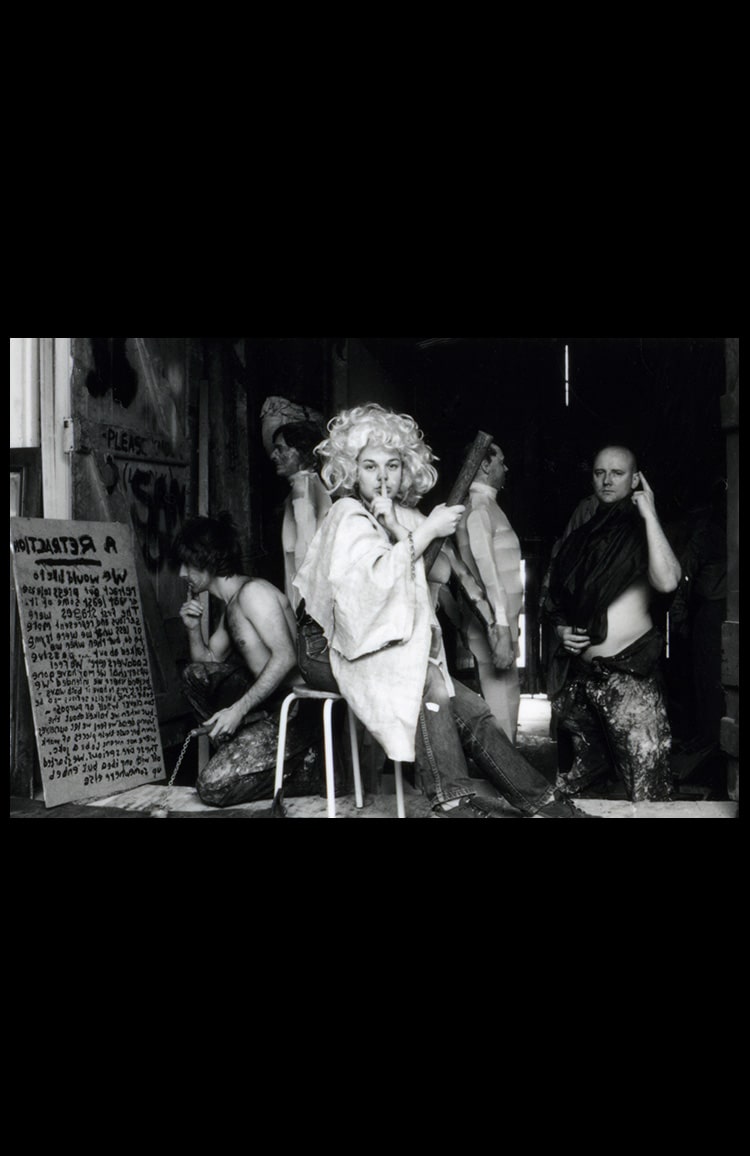

IN__Talking about posing, I think your activities as an artist can be split crudely into two roles; there’s the Milly Thompson who was a member of the London-based art collective BANK for 10 years from the early 1990s, where all of your artistic activities were subsumed within the joint ego of the group (you describe at times even going so far as to hold on to the same brush and trying to paint at the same time) and then there’s Milly Thompson the studio painter who, after leaving BANK in 2003, now spends most of her time making oil paintings of female nudes reclining on the beach or contorted into unnatural positions, adorned with extravagant accessories and showing in a more traditional gallery system. Can you talk about your involvement in BANK and why you decided to leave to focus on its polar opposite, painting, which is a very solitary practice?

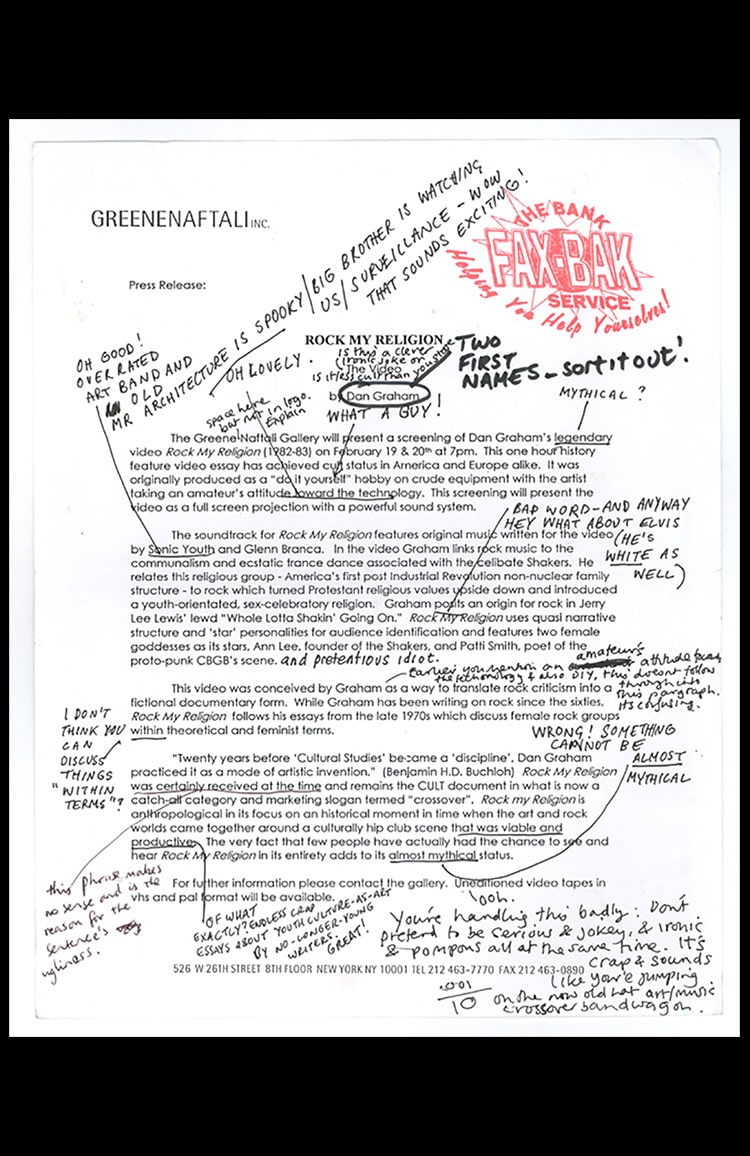

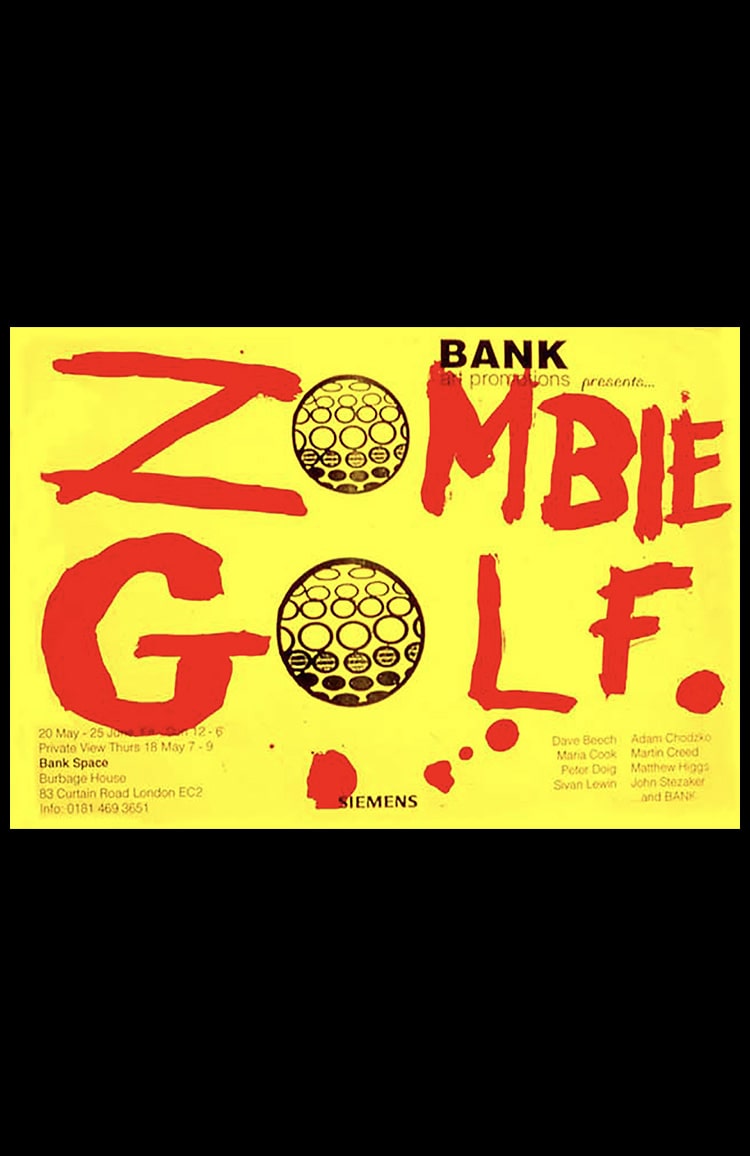

MT__BANK was exciting against the backdrop of an as yet to be Frieze’d art world. We could see it coming though, everyone. We could see the proliferation of art galleries and their professionalising nature. We enjoyed pointing out the bullshit, but also wholeheartedly acknowledged our own lame aspirations towards being “professional” artists.

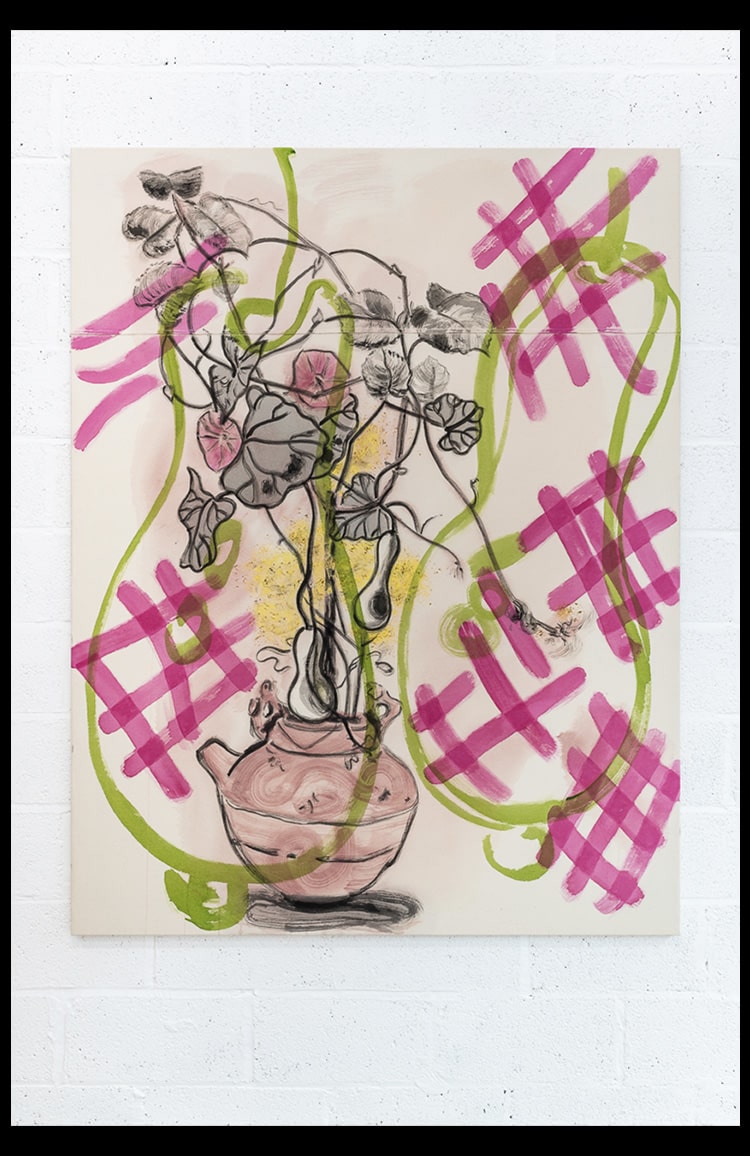

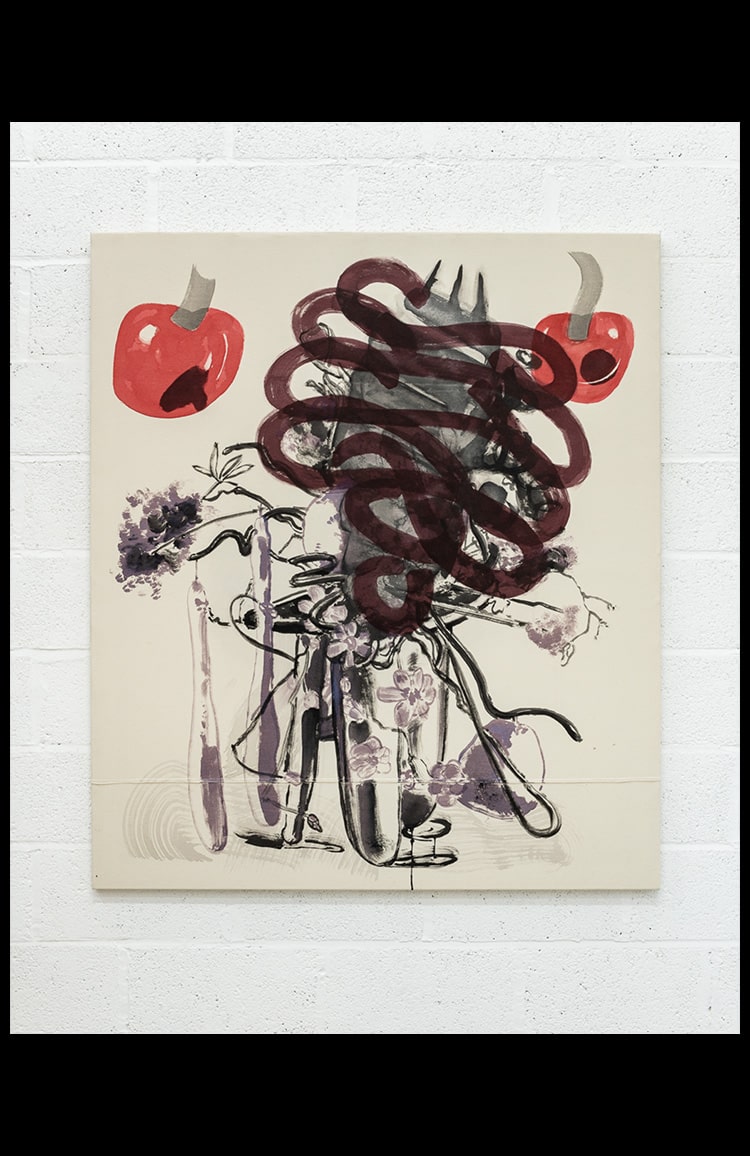

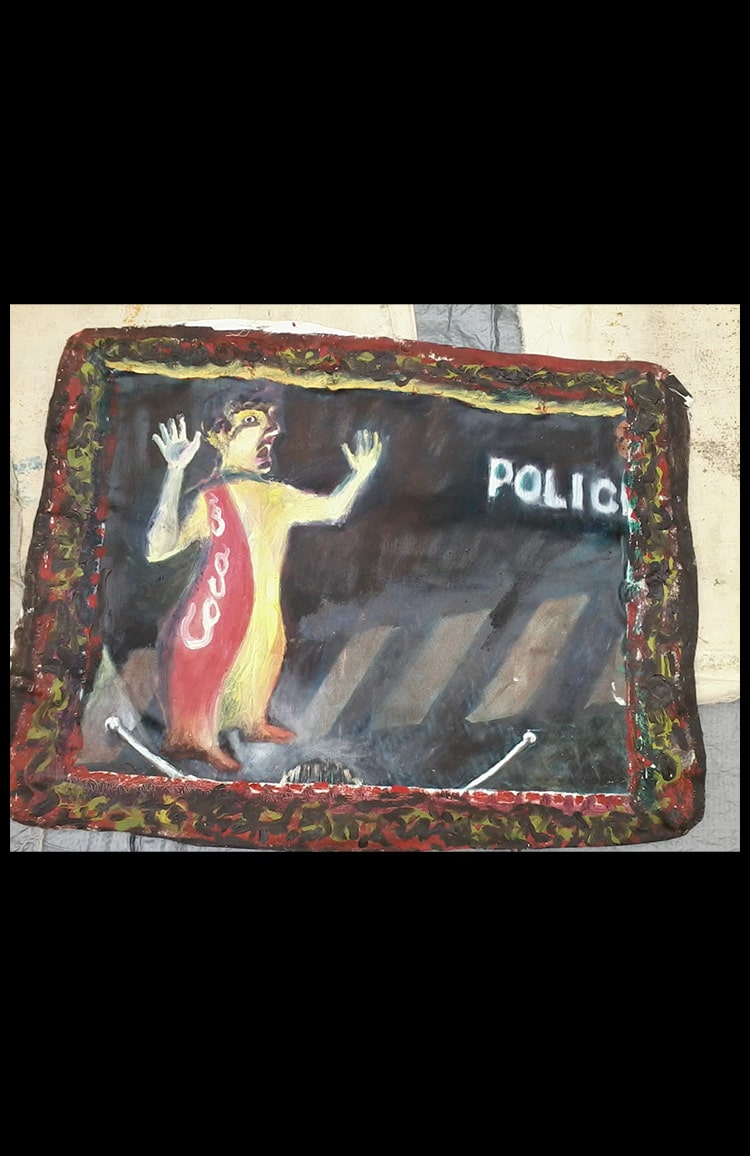

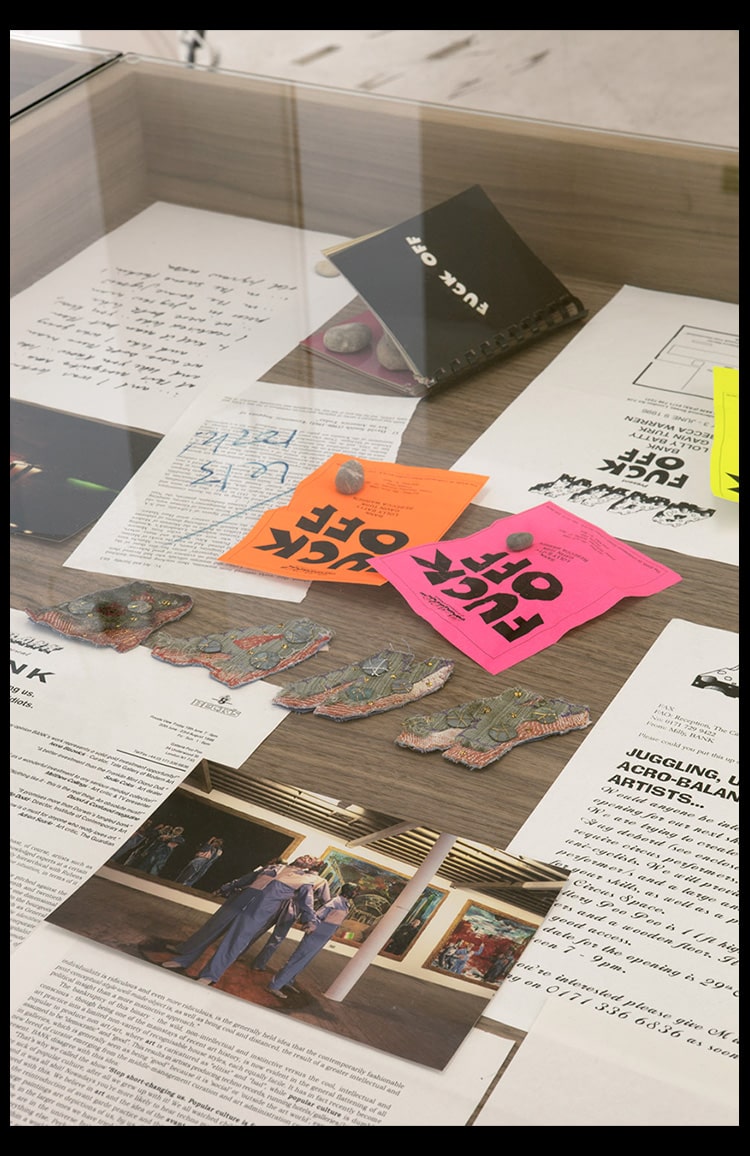

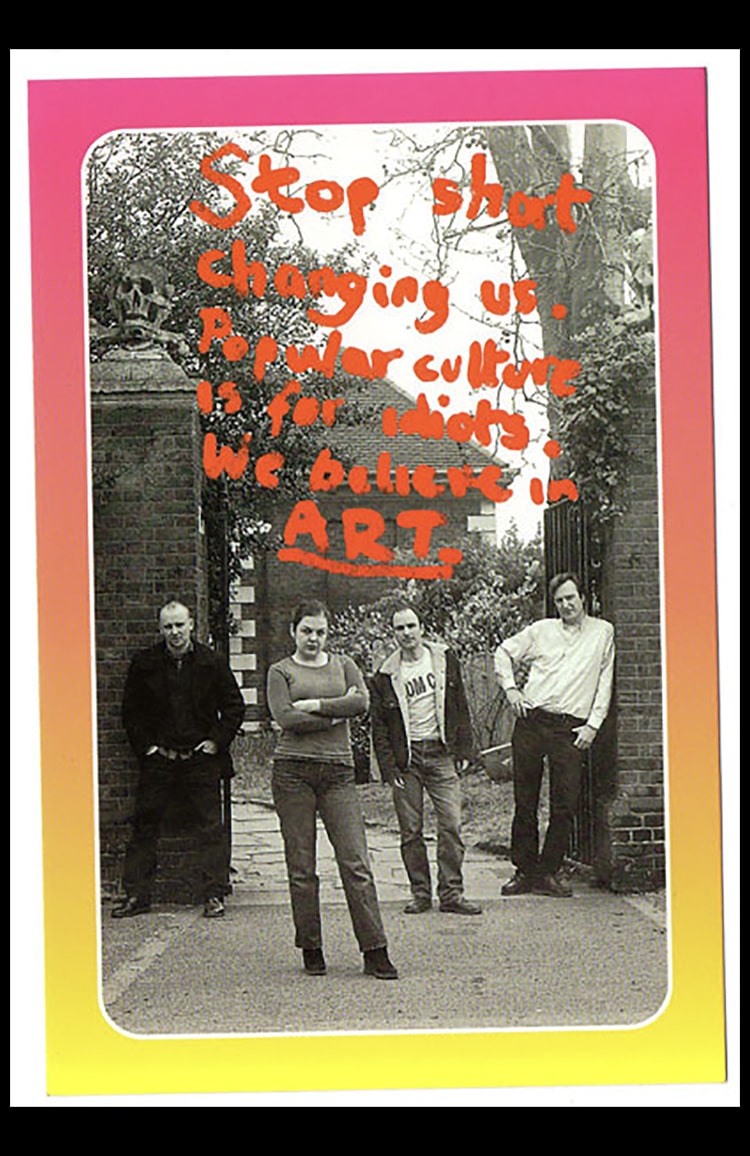

BANK was particularly interesting as a collaboration because we actually acted as if we were a single entity artist; we worked on everything together and subsumed our natures into one gigantic ego. We made art that ran against the trend of professionalisation, so the sculptures and installations we made had a throwaway quality to them. The written word was also important to us; how it functions both in titles, press releases and in the work itself.

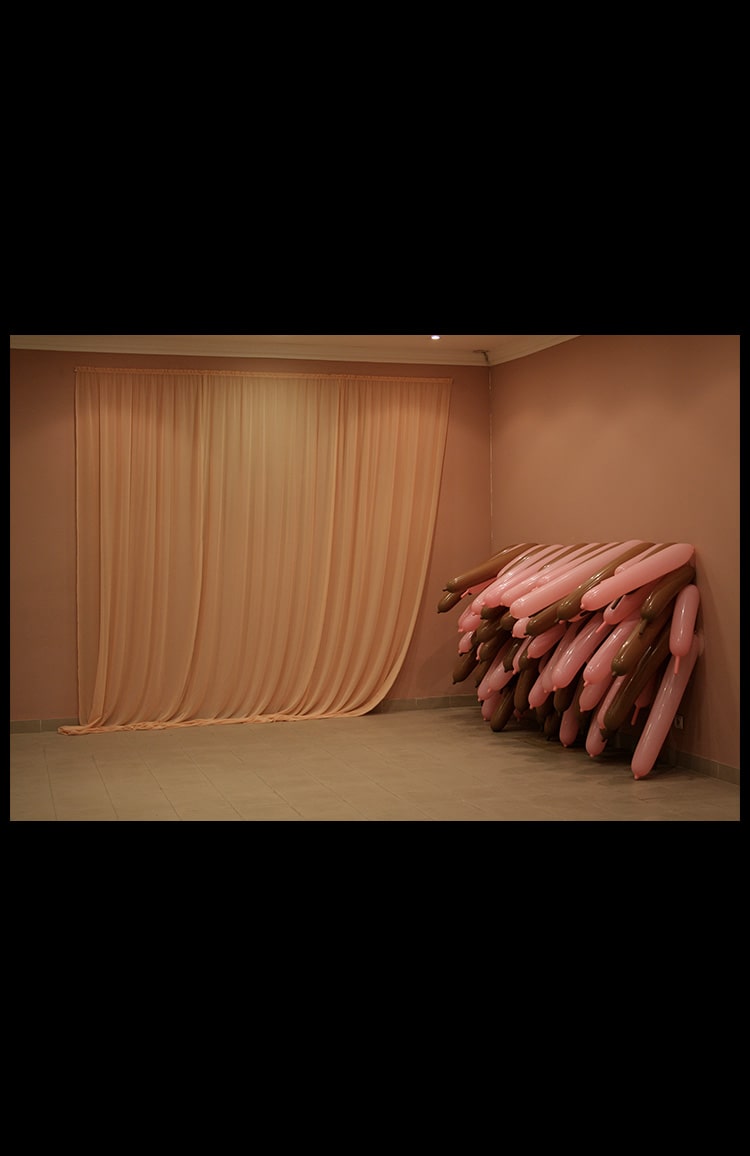

I left because I wanted to explore my own thoughts, perhaps also my “woman-ness”, which had been subsumed into an otherwise male group. I left BANK, as you say, in 2003, and didn’t do a show where I was truly happy with my own work until 2011 with ‘Saucisson Chiffonaire', a solo show within a group presentation I did at Caribic Residency in Lisbon, Portugal. It took me a long time to understand what I wanted to do, I tried video and printmaking, and I must say that for years I was miserable because I was a bit lost and yearned for collaboration but, ultimately, I have found my voice. I’ve ended up painting women in psychologically sun-drenched landscapes.

IN__In some senses BANK makes me think of the activities of another group that arose around the same time, the New-York based art and fashion collective Bernadette Corporation (founded in 1994). This was essentially a group of young graduates from Brown and Columbia University who went through the motions of a legitimate corporation; they would dress up in a suit and briefcase and go to the studio every day like they were going to a job on wall street, put on fashion shows and stage convincing-looking editorial photoshoots, even though there was no real ‘product’ behind the brand. BANK, being British, was maybe a less slick, slightly angrier version. The artist and art critic Matthew Collings described BANK as "surly, self-destructive, self-conscious, introspective attitude - combined...with critical intelligence and a flair for spotting weaknesses in the art system.” Would you say that’s accurate?

MT__Yes, spot on.

IN__Do you see any similarities between Bernadette Corporation and BANK and did you have any contact / relationship with each other?

MT__I’d say the difference between us and them is that they were self-consciously cool and we were just cool. We didn’t have anything to do with them as far as I can remember. They were very “New York” and we were provincialised in London. I did like their work, they were good at looking at layers of hypocrisy and structures around protest and capitalism, but BANK was more concerned with making art about being artists. Like you say, Bernadette Corporation wore suits and carried briefcases… BANK’s studio was freezing, dirty and we wore overalls, hats and scarves. Our studio had mice and other rodents.

IN__So, if BANK came up just before Frieze became a thing, how did you feel about seeing the YBA’s come up in real time? In a way they were doing something similar to BANK but taking the reverse approach, by embracing the bullshit rather than railing against it.

MT__Yeah, I think you could probably split the YBA’s into different categories. It’s such a spurious term, because if you think of artists like Abigail Reynolds, for example, she was meant to be a YBA, but you wouldn’t really know it from looking at her work. I think the term ‘YBA’ always had a homogenised edge. I think it was ascribed to a group of people after the event to try and pull them together. We weren’t so conscious of it as a term at the time. When I think about the YBAs I think about the fact that, although they didn’t all embrace the idea of making money, most of them actually did end up making money because of Damien Hirst - he was just so brilliant at that.

Damien Hirst completely defines what a YBA is - he was the impresario. The other thing about the YBAs that I think defines them, and maybe I just made this up, but I have this idea that a lot of them used other people to help them make their work from the very beginning. The idea of getting somebody else to make your work at that time was still relatively new, of course Jeff Koons had done it in America and there was the idea that you needed to have money to do it.

IN__How could they afford to have other people make their work for them at the beginning of their careers, before they had money?

MT__The thing is, in the early nineties, it felt a lot easier to get money to throw around and do stuff with. Making art using high street makers was cheap and easy because every high street had a metal shop or a wood shop or whatever. One of the things to remember as well is, take somebody like Tracey Emin, she’s got a huge studio now, but at that time she was making work at her bedroom table. I think lot of the YBAs were doing that, working quite modestly from home, but then going out and getting a neon made. At that time you could go down Whitechapel High Street and it was full of neon shops. Neon was still one of those materials that was everywhere, so it wasn’t actually that expensive. I think what they used to their advantage is that they were embracing materials that were really common and commonly used.

I think a lot of their work looks flashy in photographs, but if you get up close to the work actually made during that period it’s not as slick as you expect, because they were actually working within their means. Think about those Gary Hume paintings he made with Dulux brand house paints. If you look at his ‘door paintings’, which defined the beginning of his career, they might look flash in photographs, but those early works were painted on canvas or board, so the paint has probably deteriorated and discoloured over the years. Now they’re painted on aluminium and I doubt he actually does them himself.

Then, of course, Damien Hirst managed to get Charles Saatchi to buy into him from the very beginning. It was amazing. He was just so brilliant at playing the circus master. He had an easy charming, persona.

IN__You knew him?

MT__I knew him then to smile at- I don’t know him now. The art scene in London was very small back then and we all sort of recognised each other back then and, to a certain extent there was a kind of professional, jokey animosity where we were sort of fighting each other…

IN__You competed against each other…

MT__Kind of. People used to go on about BANK being “professionally working class” when we weren’t actually working class. We were just this clique that would turn up at places and get incredibly drunk and behave really badly. Actually I think that the London art scene during the late 80’s and early 90’s was defined by people behaving badly and being drunk. There was always free drink at nearly all private views. We hunted it down.

IN__There was some of that in the YBAs too. I remember seeing a clip of Tracey Emin at the 1997 Turner Prize Debate, it was live, and she’d just been on a night out with her friends so she was really drunk and she ripped her mic off, stormed out and said she was going to hang out with her mum…

MT__Yeah, that’s why it’s probably all a bit fake because the YBA was such a loose group with very different practices. A big difference to BANK, was that the YBAs made ‘product' from the beginning, and they made them under their own names as solo artists. Contrast that with the members of BANK, who would subsume our brushes to be the same, even sometimes going as far as to actually hold on to the same brush and paint at the same time. We had no identity as a solo artist; it was always the four of us, or the three of us, because BANK was a group that lost members as we went along.