IL__What is the story behind ‘Daisies’ - the title of your current solo presentation with us?

FB__Daisies are a very popular flower in the UK. They are very common but very delicate and have many ritualistic properties. One of my earliest memories of making things was joining together daisy chains in the fields near the flats I lived in. In recent years I have also developed an interest in esoteric subjects… particularly how esoteric narratives exist as a counter to normative culture. ‘Daisies’ therefore seemed like the most appropriate title to discuss work that was essentially born out of my own personal processing and catharsis.

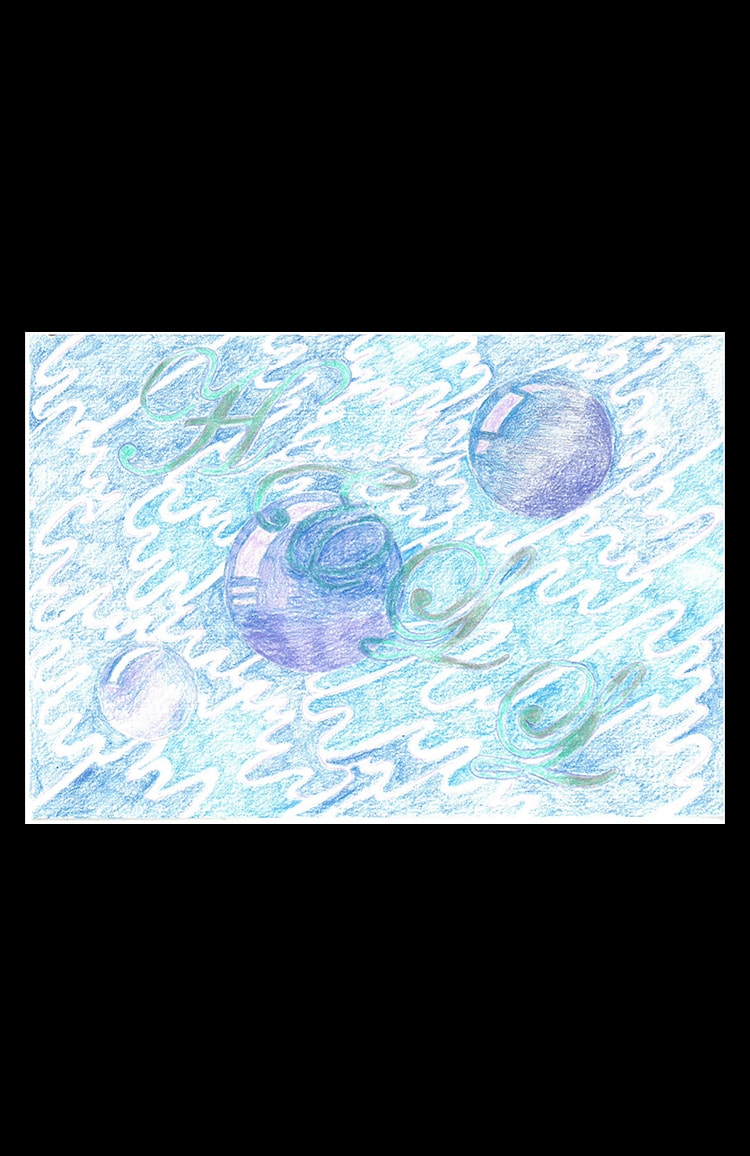

‘Daisies’ also refers to the recurring motif of daisy features in this new body of work, as well as to my younger sister Daisy. I used this daisy motif in both ‘H is for Help’ and ‘Study for a Daisy Chained Walk.’ When I was growing up I was a ‘chav’ and caused a lot of trouble, but would also hang out in parks with other children making daisy-chain garlands like some kind of folk ritual. So I think the daisy motif comes out of this collision of the personal and the mystical that, as it happens, has an unusual context within my personal narrative. It’s also a development of the chain motif I have been using in my work for a while now.

IL__Your interest in language is evident in your work. For example, your work, 'D.R. Care' and 'Hell 1' combines text and image alongside each other - how do you connect the two?

FB__Regarding the text and imagery coming together, there is an instinctive feeling of completeness and satisfaction I feel in the meeting of text and image, like how the use of strong graphics in posters make things appear more desirable. I like how things that are designed or elaborated take on an added quality of fantasy. I was always really taken by the book of Kells (an illuminated manuscript of the New Testament held in the Trinity College library in Dublin), which I saw a copy of when I was very young. I was very in awe of the layers of detail there was, even though the version I saw was a much smaller reproduction.

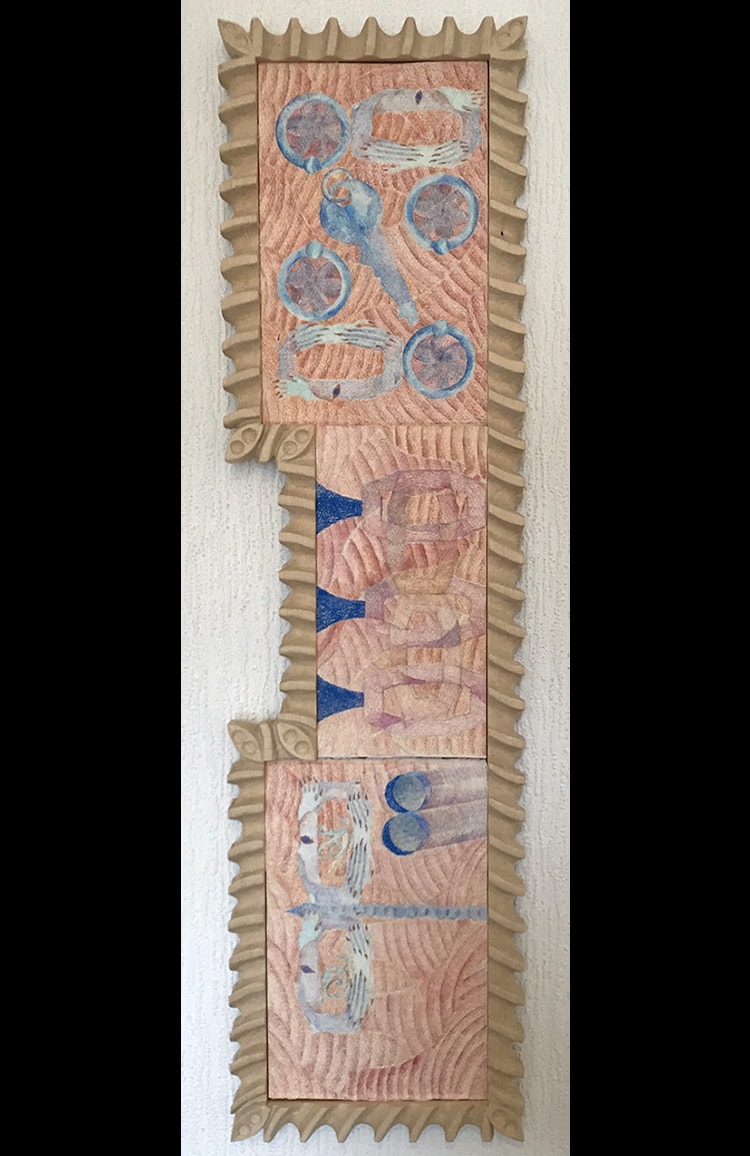

IL__Alongside your drawings, you’ve also recently been making a lot of carved wooden pieces. Often the wooden pieces serve as a frame for the drawings. 'S.A.', for example, which you are showing in your solo presentation ‘Daisies,’ consists of a drawing contained in a curving wooden frame. How did you start this series of wooden carvings?

FB__My use of wood began as a practical requirement; as a way of displaying and holding the drawings. However, since then, the wooden carvings have started to stand alone. I started combining fabric elements with these last year, which is something I am developing. The wood carving is an extension of the architectural forms in the drawing. The wooden pieces serve as anchor points, adding weight and sturdiness to the fabric pieces. The process of carving is not dissimilar to the process of how I paint.

IL__Whether it’s painting, drawing, or wood carving, the vast majority of your works are very detailed. It seems, to an outside viewer anyway, that it takes a considerable amount of time to make each piece. Does spending a long time on each work mean something to you? Do you think you might eventually return to making oil paintings?

FB__I think I am a frustrated landscape painter at heart. Although my practice has been expanding to encompass other materials, I always end up returning to painting in some form or another. I see my work as a form of psychic self-surgery. Ultimately I am still trying to render formations of internalized subject matter through painting, drawing, sculpture, and writing. I am excited to discover new combinations of materials I might have previously overlooked.

I see my works as emotional landscapes, landscapes of loss, involving a process of catharsis. Despite this I do not necessarily see the works as particularity sad or melancholy. Although my specialism is in painting, I have been using craft processes more and more in my work. The works also do often involve a lot of labour, meaning that the time involved in making becomes intertwined with the materials of the work. I have a fairly developed design before I make the pieces, although things do change in the studio. I get excited when unexpected details emerge in the work. I hope my work becomes more elaborate and intricate.

IL__Repeated motifs, numbers and phrases like “Dr. Care” disperse themselves across your works. You also incorporate a lot of images that evoke the idea of infinity such as chains and interlocking circles. How do you determine motifs?

FB__I combine text and image in my work. Both the images and the texts in my work are decontextualized. They are untethered and arranged in a method of my choosing, taking on a psychedelic quality. Repeating these motifs become keys that can be used to interpret different meanings. I think this idea of unlocking is vital to my practice, the process of understanding. Having these motifs that reemerge over and over in the work allows me to concentrate on materials and the process of making.

Recently I have been playing with this idea more in depth, both in my two-dimensional and three-dimensional works, taking the idea of ‘layering’ to a new level. I like aspects of my work to become self-generating, like a maze linking back in and feeding itself like the subconscious. I have been using holes as a motif in a lot of my work. For instance the chains, portals, and geometric ring motifs I use are based on arseholes. I also repeat the numbers ‘0’ and ‘8’ in my work; through repetition they become more than just numbers, coming to exist as separate characters. The number ‘8’ is significant to me because my birthday is the eighth of January, which is also the eighth day at the start of the Gregorian calendar. I also like that the figures ‘0’ and ‘8’ can mean both nothing and eternity. That really is the universal description of life and I think that represents how I see art making - it is what I have chosen to do with myself while I’m on earth.

Phrases like “Dr. Care” also emerge in my work. “Dr.” is an abbreviation for “doctor.” I also often think about ‘care’ when I make my work. The term ‘care’ also has personal significance for me as there’s a lot of mental health stuff in my family; I’m also had to live with some of these challenges myself. I’m a lot more stable today than my younger self, but it’s an ongoing process. Care is used a lot in relation to the treatment of disease, but it has also (annoyingly) been used out of context by the self-care industry and wellness companies.

It seems that people are often conditioned to turn their backs on people who aren’t completely able-bodied or minded, and this is also a product of capitalism and oppression. Normativity is sold to us in many forms and I feel quite critical about the lack of space that is given to things that are difficult or are disruptive. I have become more aware and angry about this as I get older. So the phrase “Dr. Care” for me resonates with these issues; it represents who I am and where I come from. It is also a reminder for myself to take care and be aware - to resist the things I do not want to become.