IN__Much of your work references America’s recent political history. I’m thinking particularly of Star Star (2006) where a figure, painted to look like the archetypal ‘wise old man’ seems to decompose into a crumpled star spangled banner. A number of your paintings are also made using only red, white and blue. You were also included in the group show ‘Make Painting Great Again’ at Canada gallery in 2016, the year Donald Trump was elected President of the United States. Considering the very rapid shift in American politics since then, are you still finding painting an effective means of containing or capturing these changes, even on a personal level?

JF__From the early nineties, around the time of the First Gulf War, I have been extremely critical of the power structures in this country. My distaste for Imperialism and macho patriarchy has always seeped into the work but, like I indicated earlier, I don’t make the work starting from a political or conceptual place. I start from a very formal, intuitive place and if the work needs to go in a more overt political direction in order to be successful I go there.

Trump is a disaster but he is also a symptom of a much bigger problem. I was born at the end of the baby boomer generation and the baby boomers have become a problem in this country because they basically failed. This sixties hippie generation sold out in the end, but they have an arrogance about them. I meet these people and we argue politics and in the end they’ll go and vote for Joe Biden or they’ll go in the middle because they’re actually deeply conservative, but they think because they went to a Jimi Hendrix concert forty years ago that they’re cool. “I burned my bra in 1972” - well so what! You know what I mean? And they feel very threatened by the progressive movement in this country because it challenges their sense of moral authority and self satisfaction.

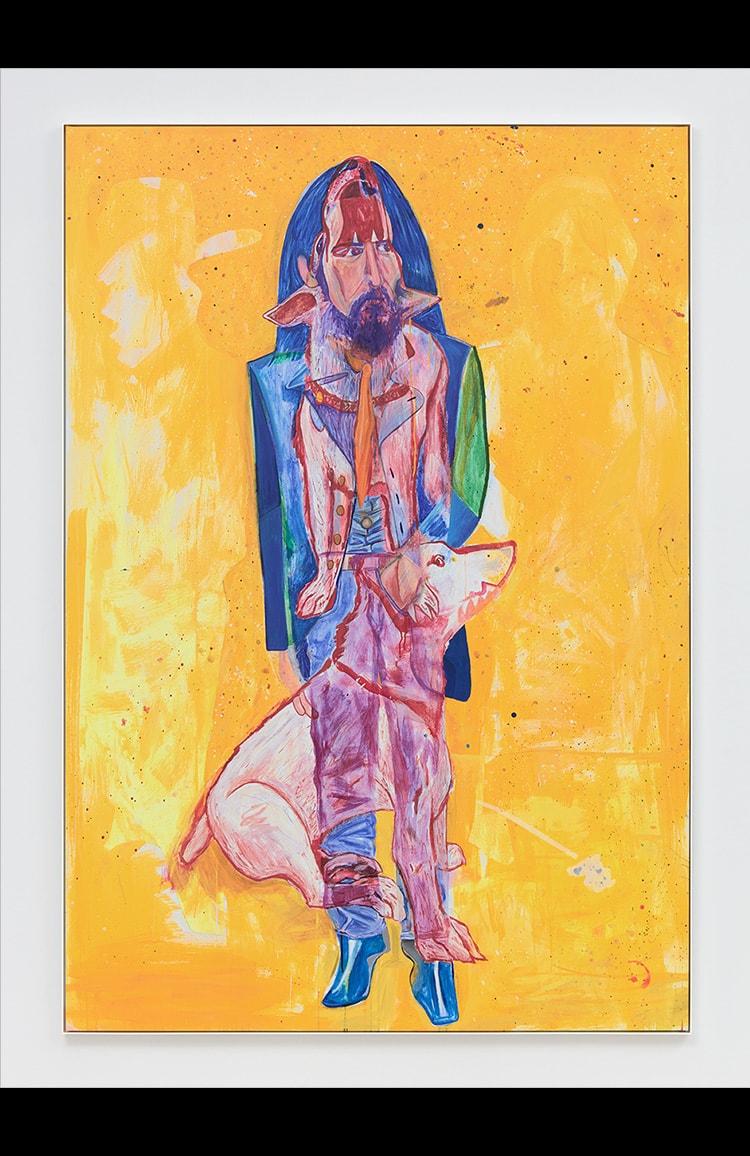

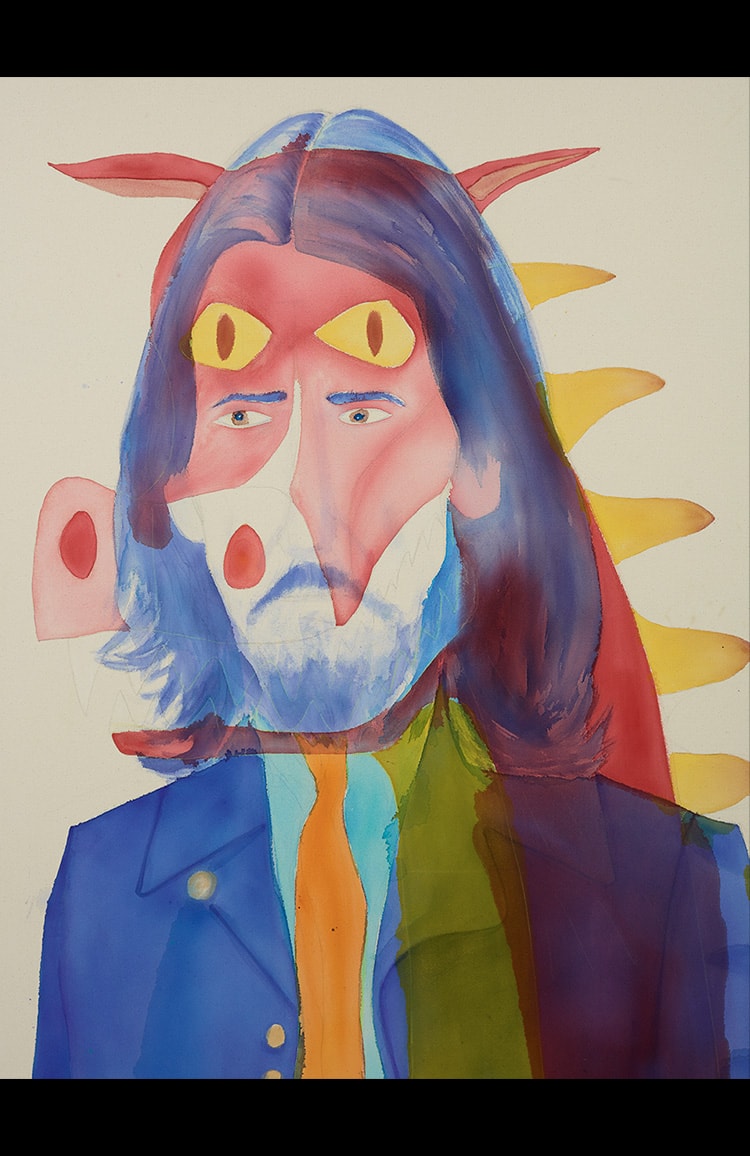

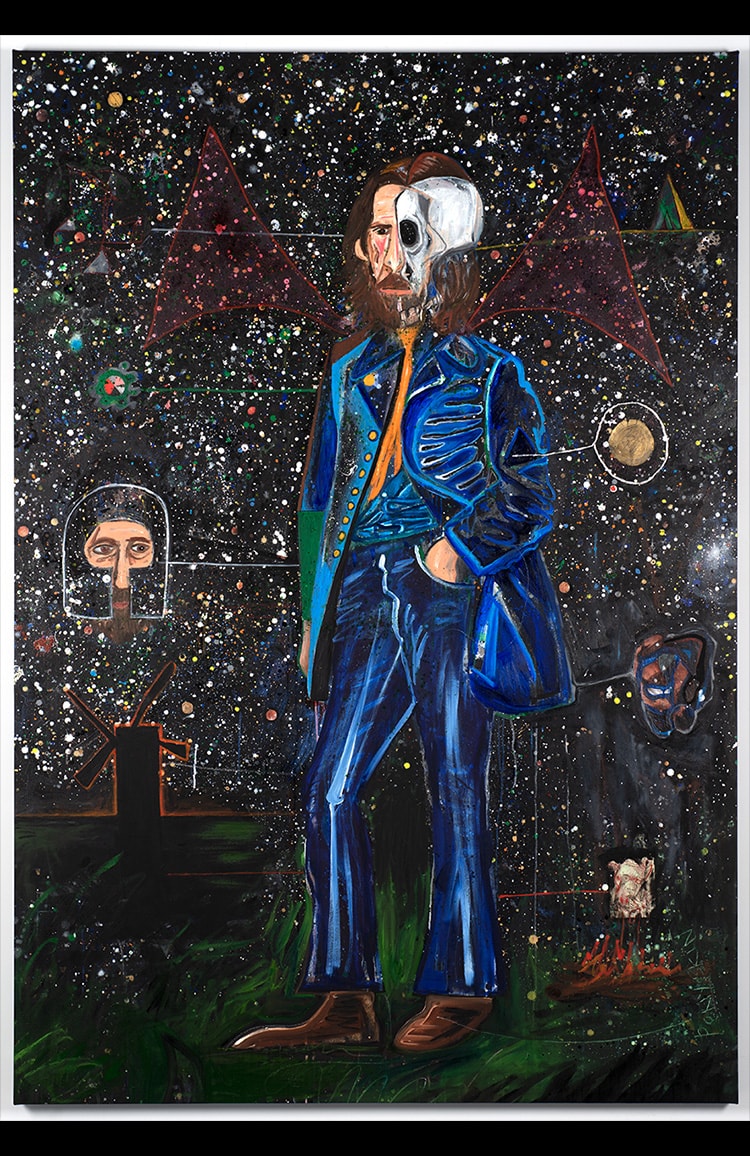

That generation’s idea of “you can have it all” is a disaster and a lot of those people still believe in that myth. For example, and I’m going to stress that these thoughts about the work have come into my head after the fact of making these paintings for all these years, I’ve painted George Harrison a lot. Part of why I find his image interesting is he’s a perfect symbol of that kind of failure. He’s someone who, on the one hand, was really spiritual and was into meditation and Indian mysticism and all this sixties mumbo jumbo. On the other hand he partied a lot, he lived an incredibly lavish lifestyle and slept with tonnes of women. It’s this boomer “I can have it all” attitude of “I can be a really mystical, spiritual person and still live like a rich playboy.” I think that kind of contradiction and hypocrisy is embedded in the baby boomer generation and these are the people who run the world. They are the ones in power and with most of the wealth and I think that’s one of the reasons why it’s so hard to get change. We’re run by a group of people who are very unwilling to be self critical and get beyond their own self mythology.

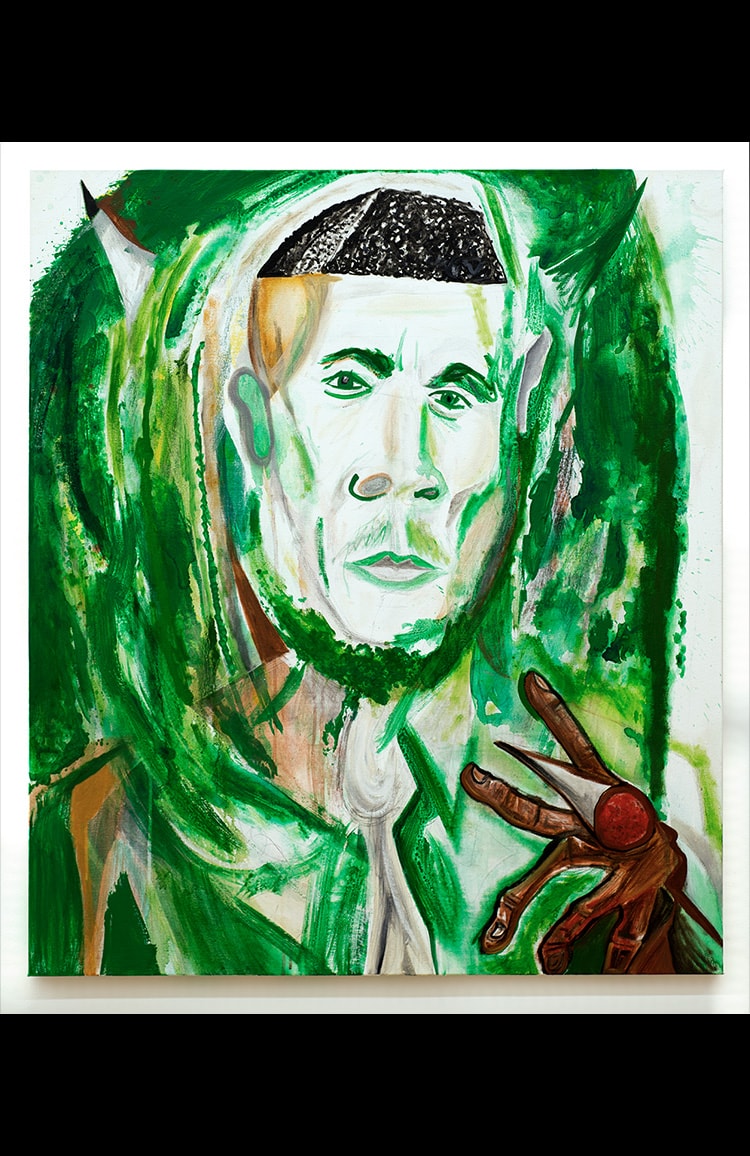

A lot of my work deals with the culture of obsession we have, particularly in the U.S., with image and how much power the brand of the person had over people. I used to get into arguments with people about Obama and his record and they would be shocked when I told them the stuff that he actually does. They don’t know. All they know is that he looks cool, he gives great speeches and he hangs out with Jay-Z so he must be great… but Obama did stuff that even Bush didn’t dare do and when I tell them that they don’t know what to say. It’s interesting how so many people are swayed by image and the surface of things. My generation was very much like that.

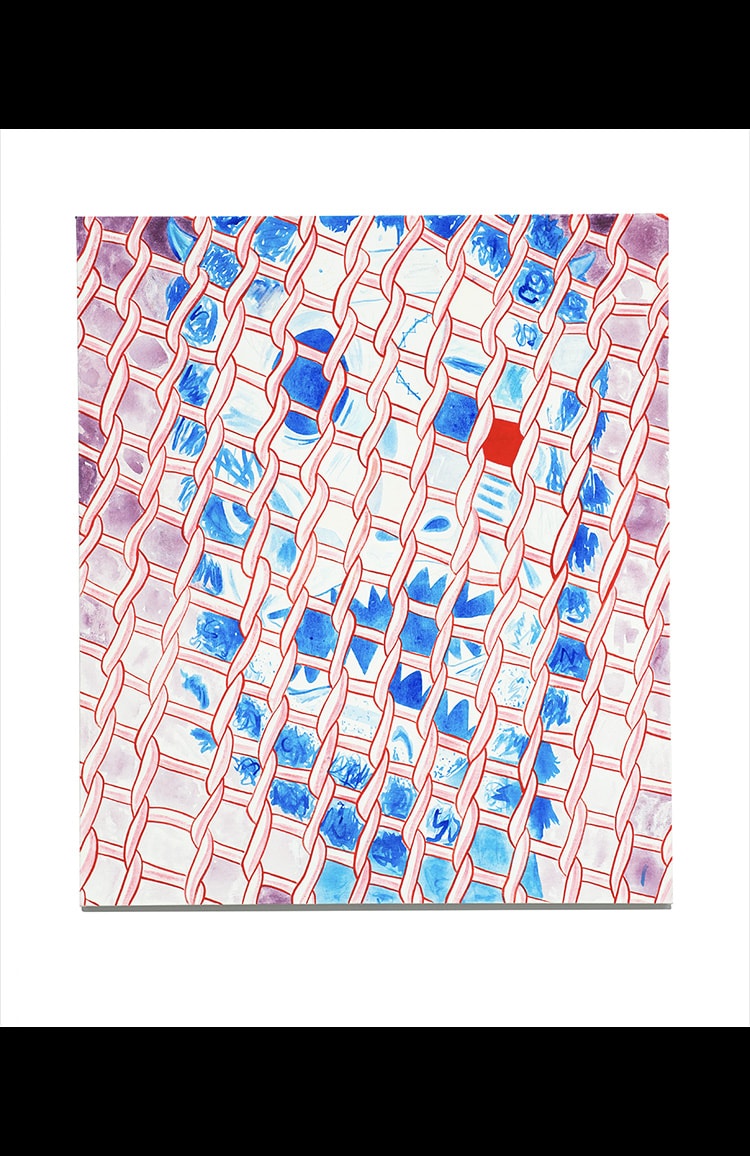

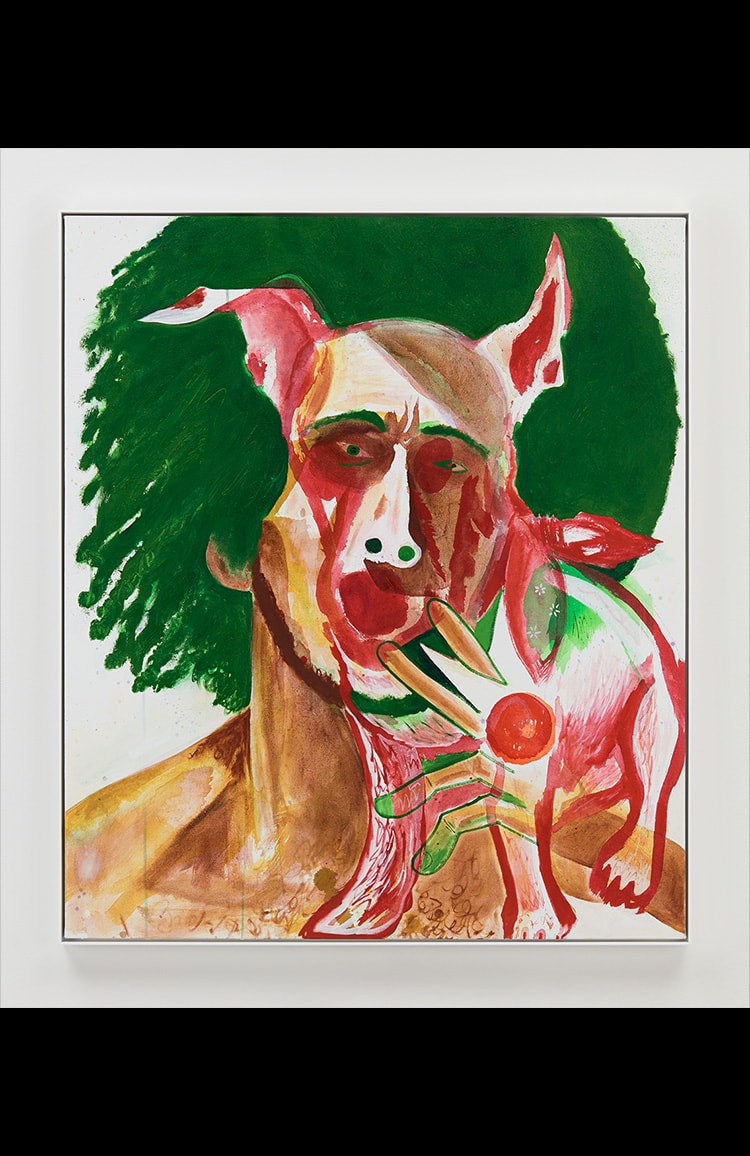

IN__A foam clown nose features in a lot of these works. It seems to me a very simple way of importing satire into your work, literally gluing it on to the canvas. Can you talk about why you started using this as a motif?

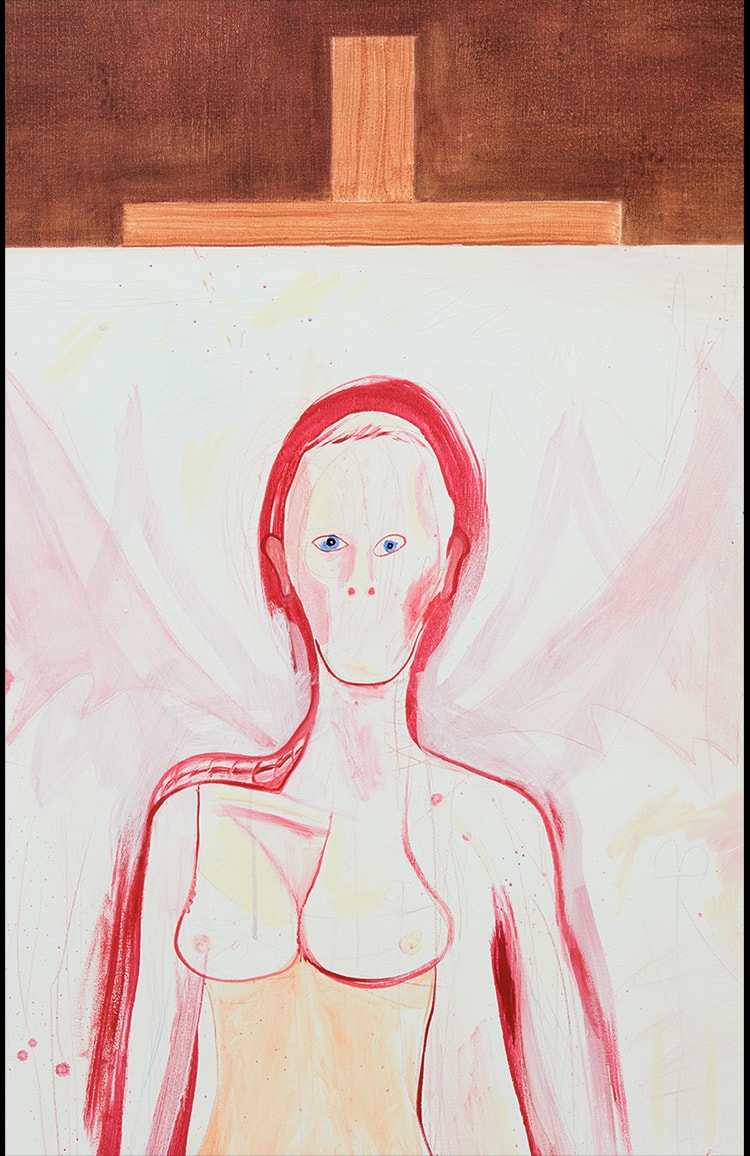

JF__As a painter you are always looking for ways to activate the surface. I saw the clown nose as a kind of anchor in the middle of the painting. I had read that the artist Barnett Newman saw his red paintings as blood-soaked and I also saw the noses as blood-soaked sponges.

IN__You said you’ve been very cynical when thinking about these events, feeling like nothing will change. So I’m wondering how you feel making these paintings at this particular moment in time - do you think they can be a legitimate form of protest?

JF__I think the paintings are more a bearing witness to events than a protest. My work feels like it’s becoming more accessible as more and more people realise how fucked up the world is. I wish I was wrong. *Laughs* I may have been overly pessimistic when making those paintings for all these years but, as it turns out, things are as fucked up as I thought they were.

Also, with the specific images I deal with, there’s a sense of probing images deeper. I was thinking about Andy Warhol and his paintings of celebrities, which I’m a big fan of. That kind of approach, of digesting these images so uncritically or to reflect the culture back in such an unemotional, objective way doesn’t make sense. I’m not overtly an activist and my work isn’t political, but I think my paintings reflect the times in a way that makes sense to now.

IN__I think to reflect or “bear witness” to something you have to take an outsider position in some sense. I mean, with Warhol, his way of doing it was he became such an extreme insider that his insider position itself became extremely alien. He sort of went out the backdoor and became an outsider again. I feel like, as an artist, you’re always trying to balance the inside with the outside, not just physically but psychologically and emotionally as well. At the same time, it’s your job to communicate and to do that you need to show your work. So I’m wondering, now you’ve become more of an insider in terms of your career, as you’re now a recognised artist and have representation etc., do you find it harder to keep that balance?

JF__I think in the last couple of years I’ve been getting more opportunities and more venues to show the work, but I think I’ve been so on the margins of things for so long that it’s become a part of my DNA. I live in a place where nobody else really lives and, even before this whole pandemic I didn’t really make the “scene” very much. At the same time, I do know a lot of people. It’s sort of an insider-outsider reality. I’m not an outsider artist. I’m not completely disconnected from things. But at the same time I function pretty much in my own lane of activity. I’m not interested in the lifestyle or becoming a celebrity artist… that is just totally uninteresting to me. Like you said, you make the work so people can see it. That’s very important, though as a sidenote I think most artists are frankly better off not being seen or heard that much.

IN__I think the way you appropriate is interesting because the era in which you were making them, from the early nineties and onwards, and the kind of satirical tone of the works would suggest them to be ironic. But they seem too obsessive and fanatical to me for you to be taking the kind of cool, dissociated position that irony needs. You’re too close to the work. They remind me of Chris Martin’s paintings and the way he sees his paintings in a talismanic, functional way. I was wondering if you see your work as having a kind of personal or spiritual, chaos magick kind of function?

JF__Yeah, I think any work that is powerful has to be like that on some level. I think Donald Judd is like that. There’s something extreme and crazy about his work but it manifests itself in a very orderly fashion. So I think any artist that is really interesting has some magical urge to create. I think a lot of artists tend to create micro worlds where you where you can gestate these sorts of obsessions. I think it’s a very natural way to work. From Picasso to R. Crumb to Louise Bourgeois… I see all these artists as connected. They all function in their own private worlds. Now we’re in such a political moment, you have to discuss these things, but for me they have to be absorbed into this micro-personal world. I guess that’s how you, as an artist, condense these things and make sense out of it. You bear witness through producing these objects and hopefully they’ll have some power and resonate. That’s our job.

IN__You generally paint using oil or acrylic, sometimes using pencil, charcoal or aluminium foil, however these are generally all contained within the straight edged frame of wooden board or canvas… Can you talk about the paintings you made in the early nineties on suspended sleeping bags? These stuck out to me amongst your other works.

JF__I started using the sleeping bags because they were cheap and could even be zipped together to make bigger pieces. The surface of the sleeping bags generated a lot of interesting painting events. Rauschenberg’s bed at MOMA was also an inspiration.

IN__I remember watching a Dr. Dre interview from when he was in N.W.A. where he said that he never looked at producers or musicians that he liked when composing his beats because he loved them too much. He felt too reverential to them, the reference became something heavy rather than material he felt free to mould. In a conversation with the painter Joe Bradley you talk about Philip Guston as being the “great shadow” you felt you had to “get out from under” because he had already done what you wanted to do. What is it that Guston did that you felt, at that time, you wished you had done? What are some of the strategies that you used, as a young artist, to try and take that and form your own work from it? Do you feel like you’ve managed to shake him off?

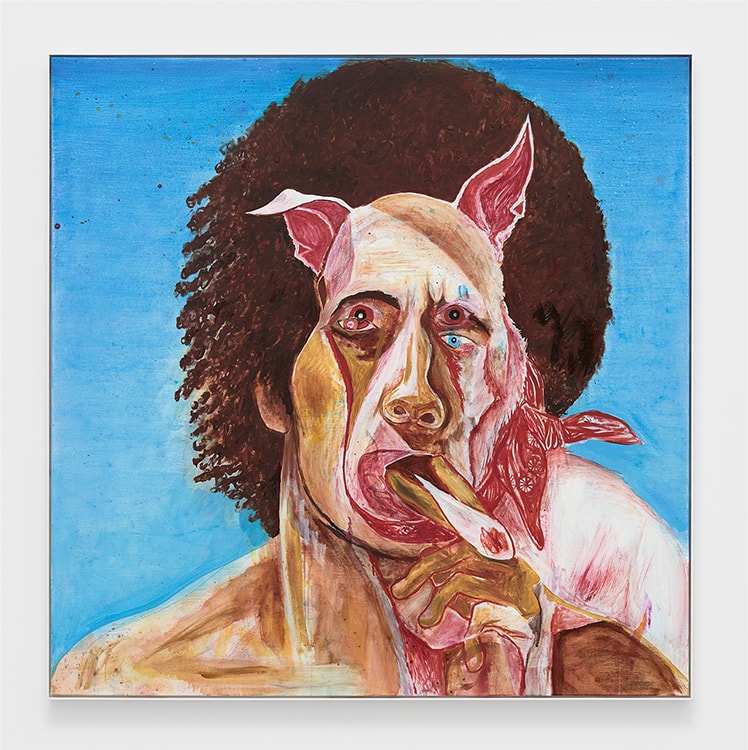

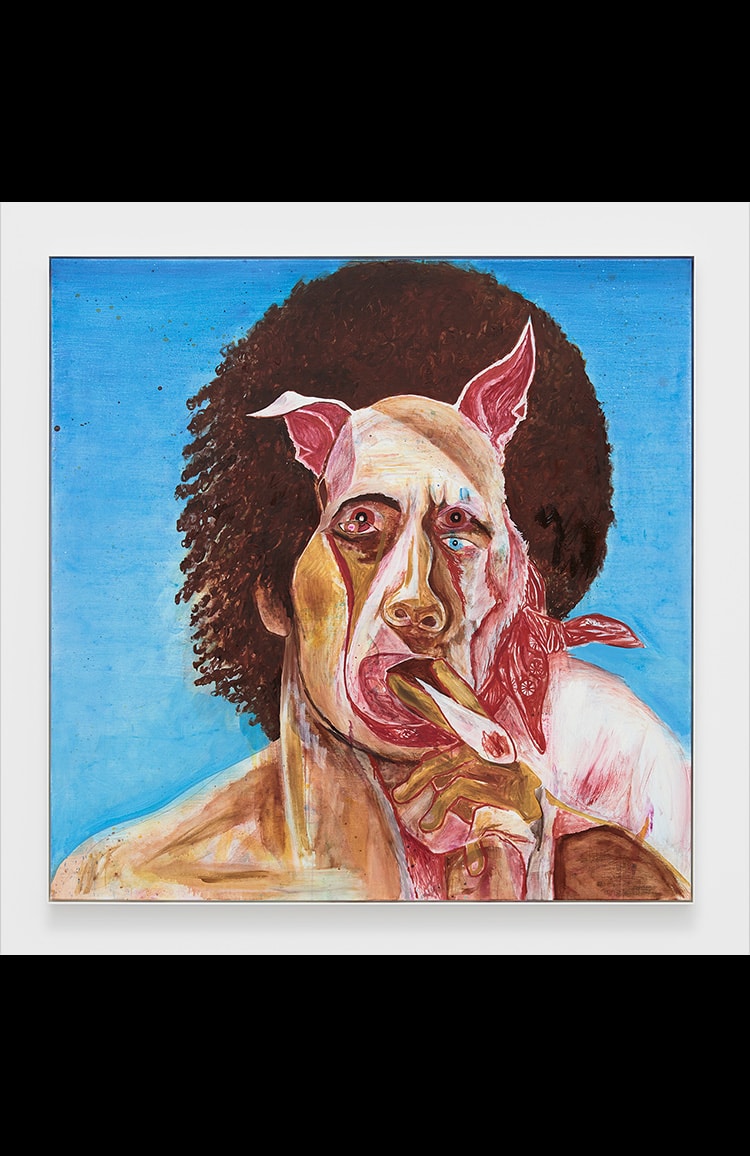

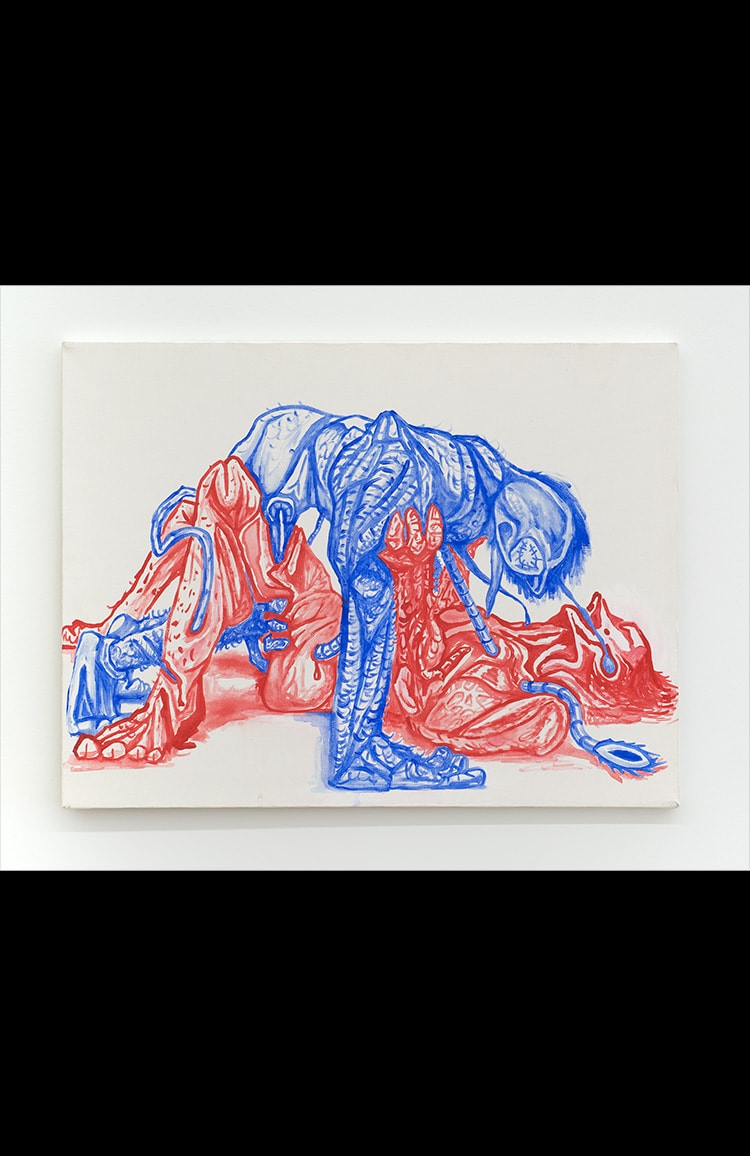

JF__Guston came up with a perfect fusion of the graphic narrative language of comics and New York school painting chops. Once he started the late work it doesn’t really change much in terms of how he paints. There is no reason to, how could it get better? The images just keep expanding. My initial idea was to make my imagery more extreme as a way to create my own space. Movies like Scanners, The Thing and classic eighties horror were a big influence. Over time the gore element receded as it became less necessary and the work did develop its own distinct feel or look.

IN__In this same interview with Bradley you describe viewing your appropriated references as dismembered body parts; making a painting for you seems to be a process of unifying them into a functional whole. How do you think this approach differs from some of your peers’ use of appropriation? Do you often have an image of this final “whole” in mind when building up your paintings?

JF__I have never been interested in delving into the kind of Pictures Generations appropriation that has become very dominant. When I do use images of pop stars or politicians it is more related to Francis Bacon and his obsessive use of certain photographic images with the intent of personalizing and morphing those images so they become more of an armature for constructing a painting. I treat each painting as its own unique problem to solve and sometimes I might need to loosen or tighten up something, or move among different styles as necessary. I usually have an idea of the final image, but it can change.

IN__Your paintings use eccentric, idiosyncratic forms that sometimes seem to be a series of your own personal jokes. I’m wondering if you ever got branded an “outsider” artist when you first started exhibiting? How did you try and navigate the way the audience read or experienced your work, if at all?

JF__I have always been attracted to the idea of the artist on the outskirts of things, like the William Burroughs character in On the Road or Alain Delon’s character in Samurai… being on the edges where the cracks show. Regarding an audience I hope they like the work, but I don’t worry about how they interpret it. That’s not my job.